'Abdu'l-Bahá on Humanity's Ability to "Break" the Laws of Nature

Across his talks, tablets, and letters, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá returns again and again to the dynamic

relationship between humans and the natural world. It is no accident that Some Answered

Questions opens with a statement on nature. He characterizes the human intellect as a force that

allows humans to “resist and oppose nature.

“Man is able to resist and to oppose Nature because he discovers the constitution of things, and

through this, he commands the forces of Nature” [1]

He characterizes human intellect as a force capable of “resisting,” “dominating," and

“controlling” natural constraints. Most striking of all are the statements in which he describes

human beings as able to “break” the laws of nature.

“He wrests the sword from nature’s hand and uses it against nature, proving that there is a

power in him which is beyond nature, for it is capable of breaking and subduing the laws of

nature” [2]

Interpreted literally, these statements could be misconstrued as suggesting that human beings

possess a supernatural capacity to negate or suspend the fundamental laws of physics, elevating

human beings to the status of miracle workers, seemingly empowered to override physical

constraints.

This article contends that his position is more subtle and nuanced than a literalist reading of these

statements would suggest. Rather than treating this as a claim about miracles that suspend

physics, this paper contends that it as a claim about a distinctive kind of causation tied to the

rational mind. Thus, the act of “breaking” nature’s laws represents not their cancellation but their

realignment: the capacity to comprehend natural forces and bend them to serve humanity’s needs,

most clearly exemplified in technological inventions.

By examining three specific examples, namely psychological resilience in human development,

and the human engineering of lunar trajectories, this paper explores the novel approach of

‘Abdu’l-Bahá to human powers and complexity.

## Lawful Defiance

An airplane does not break any physical law. Its engines obey conservation principles, its

structure is constrained by material strength, and its trajectory is a solution to gravitational

dynamics. Its success depends on regularity: predictable combustion, predictable inertia,

predictable orbital mechanics. In that sense, the airplane epitomizes obedience to laws of nature,

not an exception to them.

Yet the airplane raises an interesting philosophical question, a question that is implicit in ‘Abdu’l-

Bahá’s statements on nature.

An airplane does not violate laws of nature, but can nature produce it?

Put differently, can something be operationally compliant with natural law and still be

“unnatural” in another sense?

A logical way to draw this distinction is to separate (1) the laws an entity obeys from (2) the

causal narrative that could account for the entity’s existence. Artifacts and organisms share the

first characteristic: both are physical systems subject to the same natural constraints. They may

diverge in the second. Many argue that a spider’s web, or a termite mound’s ventilation

structure, arises through processes that do not explicitly represent goals, even if they appear to

yield goal-directed outcomes. An airplane is created through an intentional chain: abstraction,

modeling, deliberation, error-correction, and coordinated planning. Its distinctiveness lies not in

floating above nature but in embodying intelligent-mediated processes for its formation. As

‘Abdu’l-Bahá puts it

“Man is not the captive of nature, for although according to natural law he is a being of the

Earth, yet he guides ships over the ocean, flies through the air in airplanes, descends in

submarines; therefore, he has overcome natural law and made it subservient to his wishes” [3]

This philosophical inquiry leads to the concept of “natural unnaturalness.” An artifact can be

natural in its efficient causes (materials, forces, energies) while it could be “unnatural” in its

formal organization, in the sense that the organization may not be plausibly attributable to an

unguided physical evolutionary process across time.

In this light, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s language of “breaking and subduing” can be read as pointing to

a deep philosophical puzzle; not that evolution can generate lawbreakers in the supernatural

sense, but whether non-intelligent evolutionary processes can generate law interpreters and law

users , beings who view nature’s constraints as something to be understood and redirected.

Against the Current Within: Confidence Beyond a Lifetime of Negation?

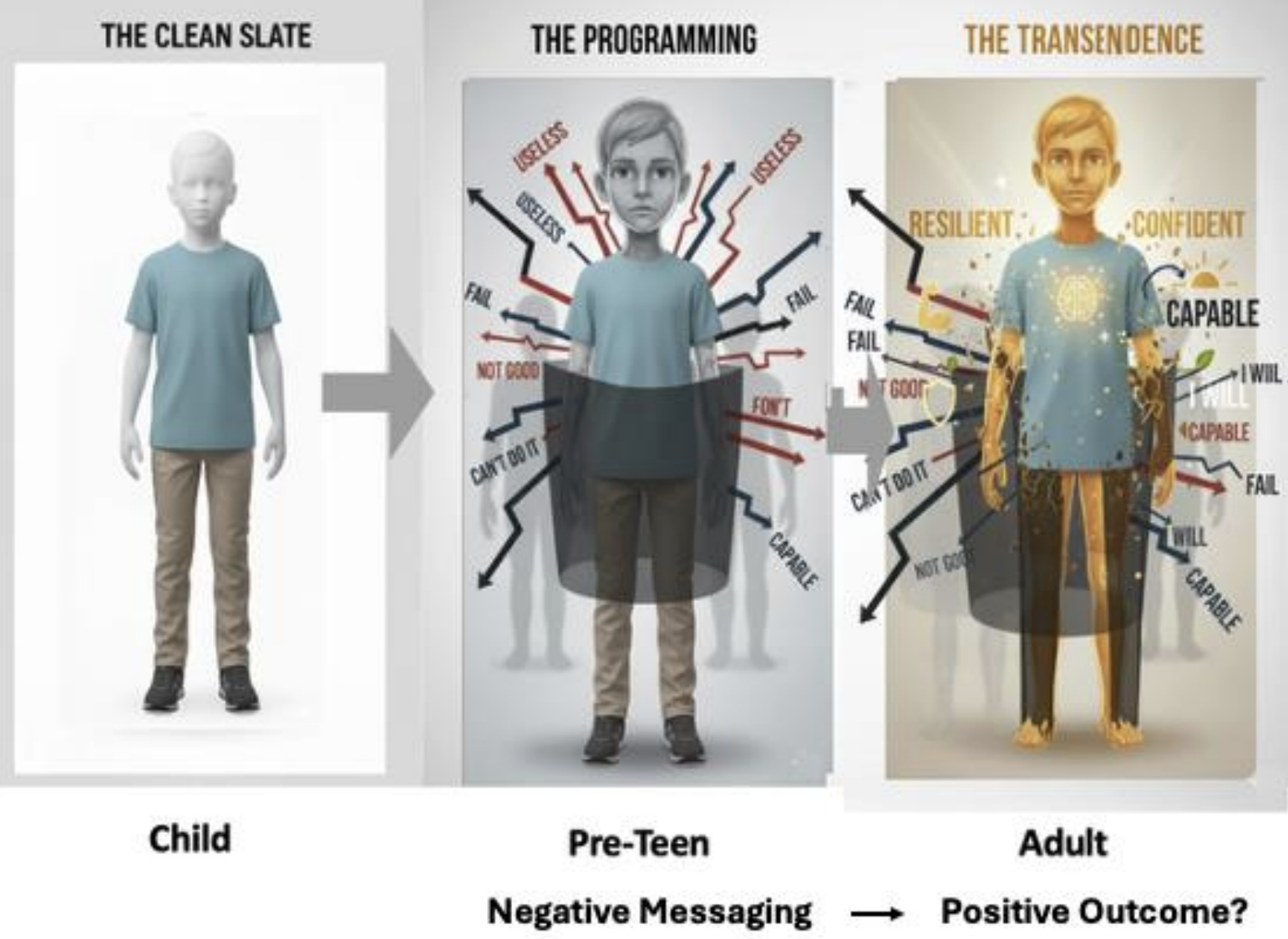

To explore philosophical questions raised by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, let us have a thought experiment.

Imagine a child who evolves and grows over a long time, measured in millions of years. He

receives consistent negative messages: “you are inadequate,” “you will fail,” “you do not

belong,” “you are a loser.” The thought experiment is deliberately extreme. It frames “negative

programming” as the totality of the child’s external forces, so that adult confidence appears

impossible if the child is only an aggregate of those inputs. If the child’s psychological profile

were nothing more than the imprint of external influences, one must ask: why would the child try

to “reach” for confidence at all, let alone ultimately “become” confident? On a purely externalist

picture, the end state should mirror the long external input: shame, timidity, and learned

helplessness. Yet we are asked to imagine the opposite: the child matures into a confident adult.

The route to confidence is not magic but a second-order capacity: the ability to reflect on one’s

own mind, step back, and intentionally reorganize one’s conditioning and upbringing. In doing

so, a person can stand apart from one’s formative history and through deliberate practice, rewrite

the psychological script into confidence and resilience. It is in this discontinuity between

environmental input and behavioral output that the philosophical dilemma appears again.

If the child were only an aggregate of external influences, why would the child ever evolve

towards confidence at all, rather than ultimately mirroring the long history of negative

programming?

Put differently: can a child, initially a clean slate yet subjected to years of deprivation and

sustained external denigration, genuinely grow beyond such conditioning, or does this require a

further capacity that can rise above those immediate psychological constraints?

The thought experiment becomes plausible only if the mind can step back from what has acted

upon it. A reflective agent can treat repeated put-downs as evidence of the parents’ shortcomings

or of the social context in which they lived, rather than as a final verdict about its own self.

Crucially, the agent can consciously reorder the mind: redirect attention, retrain self-appraisal

habits, and adopt disciplined practices that reshape its negative programming. Confidence then

becomes but a deliberate reweighting of influence, as the person tests messages against evidence,

adopts standards beyond reward and punishment, and restructures self-evaluation. The

“program” remains part of the story, but it no longer governs it.

This inward reordering can be viewed as a “lawful yet unnatural” redirection. Just as an airplane

does not violate physics yet cannot be fully accounted for by blind physical processes alone,

resilient confidence does not by itself violate psychological causality, but at the same time

cannot be explained as mere reflection of external forces. In both cases, we encounter a distinct

kind of causation. This concept-guided process remains within nature’s lawful constraints while,

at the same time, transcends nature’s local limitations and creates entities that leverage nature’s

laws against it.

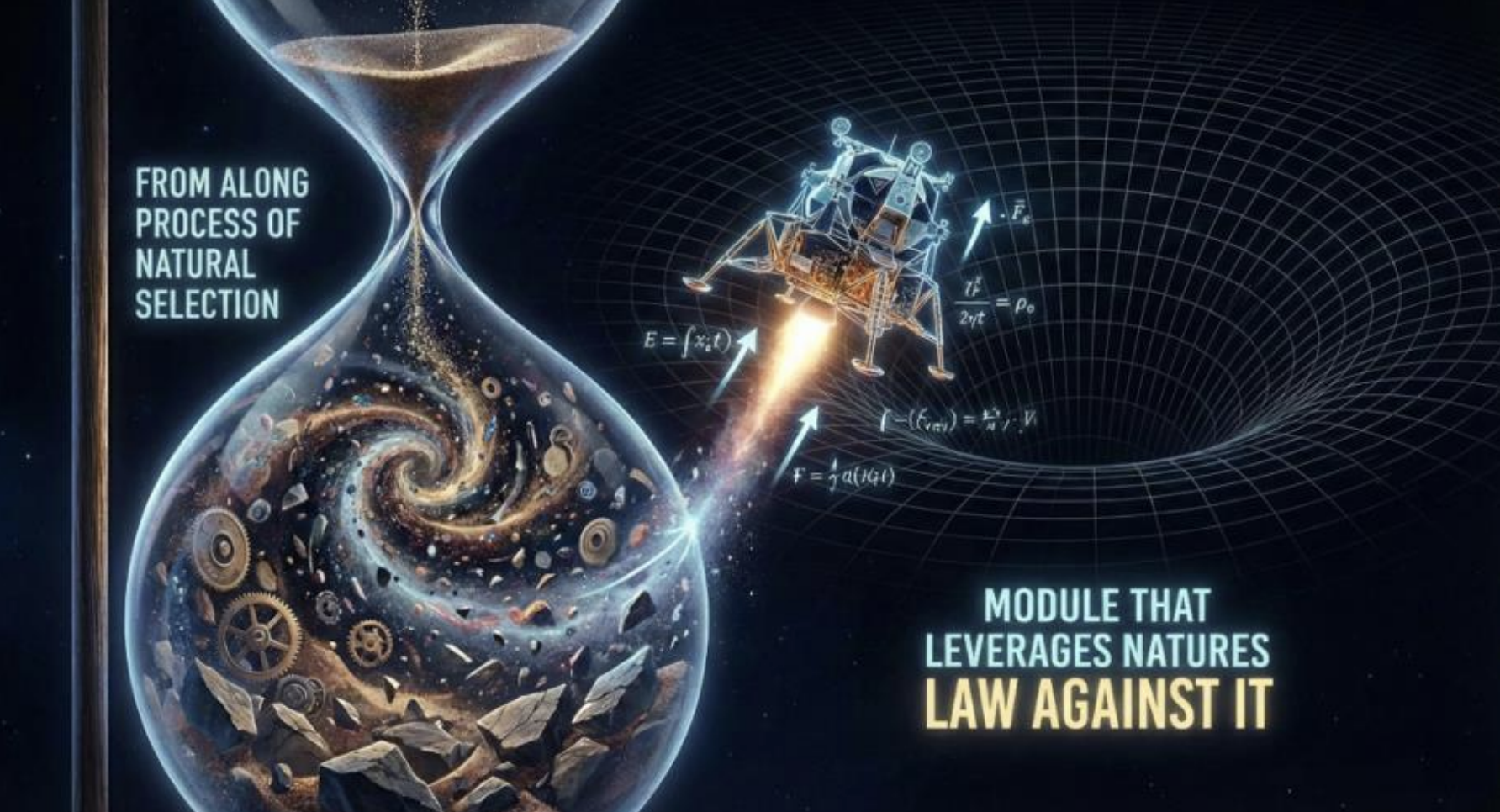

Escaping Earth’s Gravity: Lawful Flight, Unlikely Origin

To leave Earth is to confront one of nature’s most formidable constraints. Escaping Earth’s

gravity is daunting, to say the least. Near the surface, gravity continually “pulls back” at every

instant of ascent, while atmospheric drag compounds the burden. Achieving orbit already

demands velocities of several kilometers per second, sustained by controlled acceleration and

precise timing. Escaping Earth’s gravitational pull requires even more energy and even tighter

tolerances. The problem is not simply going upward. It is sustaining a carefully managed

sequence of forces long enough to shift from ordinary falling to orbital motion, and then adding

the additional energy needed to depart a bound trajectory altogether.

The Lunar Module, within the larger Apollo system that delivered it. The achievement is not a

loophole in nature but an exacting submission to nature’s regularities. Gravity is neither

suspended nor weakened. Through careful deliberation, those same dependable laws are

leveraged against their default tendencies: gravity and inertia are not resisted blindly but

calculated and recruited, so the very constraints that bind the craft to Earth become the

conditions that make controlled escape and navigation possible.

The route to confidence is not magic but a second-order capacity: the ability to reflect on one’s

own mind, step back, and intentionally reorganize one’s conditioning and upbringing. In doing

so, a person can stand apart from one’s formative history and through deliberate practice, rewrite

the psychological script into confidence and resilience. It is in this discontinuity between

environmental input and behavioral output that the philosophical dilemma appears again.

If the child were only an aggregate of external influences, why would the child ever evolve

towards confidence at all, rather than ultimately mirroring the long history of negative

programming?

Put differently: can a child, initially a clean slate yet subjected to years of deprivation and

sustained external denigration, genuinely grow beyond such conditioning, or does this require a

further capacity that can rise above those immediate psychological constraints?

The thought experiment becomes plausible only if the mind can step back from what has acted

upon it. A reflective agent can treat repeated put-downs as evidence of the parents’ shortcomings

or of the social context in which they lived, rather than as a final verdict about its own self.

Crucially, the agent can consciously reorder the mind: redirect attention, retrain self-appraisal

habits, and adopt disciplined practices that reshape its negative programming. Confidence then

becomes but a deliberate reweighting of influence, as the person tests messages against evidence,

adopts standards beyond reward and punishment, and restructures self-evaluation. The

“program” remains part of the story, but it no longer governs it.

This inward reordering can be viewed as a “lawful yet unnatural” redirection. Just as an airplane

does not violate physics yet cannot be fully accounted for by blind physical processes alone,

resilient confidence does not by itself violate psychological causality, but at the same time

cannot be explained as mere reflection of external forces. In both cases, we encounter a distinct

kind of causation. This concept-guided process remains within nature’s lawful constraints while,

at the same time, transcends nature’s local limitations and creates entities that leverage nature’s

laws against it.

Escaping Earth’s Gravity: Lawful Flight, Unlikely Origin

To leave Earth is to confront one of nature’s most formidable constraints. Escaping Earth’s

gravity is daunting, to say the least. Near the surface, gravity continually “pulls back” at every

instant of ascent, while atmospheric drag compounds the burden. Achieving orbit already

demands velocities of several kilometers per second, sustained by controlled acceleration and

precise timing. Escaping Earth’s gravitational pull requires even more energy and even tighter

tolerances. The problem is not simply going upward. It is sustaining a carefully managed

sequence of forces long enough to shift from ordinary falling to orbital motion, and then adding

the additional energy needed to depart a bound trajectory altogether.

The Lunar Module, within the larger Apollo system that delivered it. The achievement is not a

loophole in nature but an exacting submission to nature’s regularities. Gravity is neither

suspended nor weakened. Through careful deliberation, those same dependable laws are

leveraged against their default tendencies: gravity and inertia are not resisted blindly but

calculated and recruited, so the very constraints that bind the craft to Earth become the

conditions that make controlled escape and navigation possible.

Yet this technological achievement immediately reopens the more profound philosophical

quandary.

_If the module's escape depends on deliberate calculation, representation, and purposive

sequencing, what could account for the origin of such an arrangement in the first place?_

Blind processes can yield outcomes permitted by physics, but they do not, by themselves, "aim"

at configurations that harness constraints as instruments to go against them. An evolving

aggregation of atoms has no reason to converge on staged propulsion, guidance logic, or a

trajectory plan that treats gravity as a predictable scaffold rather than a barrier. The question,

then, is not whether the Lunar Module breaks nature's laws, but how a world governed by those

laws could give rise to an agent capable of understanding natural laws and intentionally turning

them against nature's tendencies. Abdu'l-Bahá has articulated the same concepts in many of his

talks.

_“Consider, for example, that man according to natural law should dwell upon the surface of the

earth. By overcoming this law and restriction, however, he sails in ships over the ocean, mounts

to the zenith in airplanes and sinks to the depths of the sea in submarines. This is against the fiat

of nature and a violation of her sovereignty and dominion.”_ [4]

Yet this technological achievement immediately reopens the more profound philosophical

quandary.

_If the module's escape depends on deliberate calculation, representation, and purposive

sequencing, what could account for the origin of such an arrangement in the first place?_

Blind processes can yield outcomes permitted by physics, but they do not, by themselves, "aim"

at configurations that harness constraints as instruments to go against them. An evolving

aggregation of atoms has no reason to converge on staged propulsion, guidance logic, or a

trajectory plan that treats gravity as a predictable scaffold rather than a barrier. The question,

then, is not whether the Lunar Module breaks nature's laws, but how a world governed by those

laws could give rise to an agent capable of understanding natural laws and intentionally turning

them against nature's tendencies. Abdu'l-Bahá has articulated the same concepts in many of his

talks.

_“Consider, for example, that man according to natural law should dwell upon the surface of the

earth. By overcoming this law and restriction, however, he sails in ships over the ocean, mounts

to the zenith in airplanes and sinks to the depths of the sea in submarines. This is against the fiat

of nature and a violation of her sovereignty and dominion.”_ [4]

Read in this light, the gist of 'Abdu'l-Bahá's claim is not that human beings cancel natural law,

but that a distinct mode of causation can arise: rational agency that understands, selects, and

reorganizes natural forces towards its needs. Ships, airplanes, submarines, and the Lunar Module

are not exceptions to nature; they are demonstrations of a new relation to nature, in which natural

limitations become usable conditions through knowledge and purposeful coordination. What is

"overcome" is not gravity or fluid dynamics themselves, but the artifact’s creator's prior

subjection to blind processes that program it to obey nature's constraints rather than go against

them. The philosophical principle presented is that "breaking" nature's laws reflects a shift in

capacity: the emergence of mind as a power that can redirect what blind process alone would

never intentionally assemble_._

**Conclusion: Emergence or Privilege?**

'Abdu'l-Bahá's claim that humanity can "break" and "subdue" nature invites a final question that

the examples in this paper have kept pressing from different angles: _can the human capacity to

redirect nature be fully explained as the output of natural processes, or does it signal a privilege

that is not explained by those processes?_

The airplane, the resilient mind, and the lunar trajectory do not suspend physics or override

causality. These scenarios succeed precisely because nature is stable, measurable, and

dependable. In that sense, "breaking" cannot mean cancellation of the natural law. It must mean a

change in relation to law, where constraints remain intact yet become usable through

understanding.

But this is where the philosophical dilemma returns. Nature can generate complexity and

behavior that appears goal-directed without explicit foresight. The more complex issue is

whether blind process can generate _law-interpreters and law-users,_ beings who can represent,

analyze constraints, compare alternatives, and deliberately organize means toward ends that

nature itself does not specify. The child thought experiment makes the point inwardly: if a person

were only a passive imprint of external forces, why would the person ever rise toward self-

revision at all? The lunar mission makes the point explicitly: if matter and life were evolving

only under local pressures and nature's influences, what accounts for the emergence of

conceptual planning, abstract reasoning, and the long discipline of experimentation that turns

gravity from a mighty barrier into a navigable scaffold?

Two broad readings are possible and should be reflected on. On one reading, rational agency is

an extraordinary but ultimately continuous outgrowth of natural history: evolution yields minds

that are capable of abstraction, and abstraction yields the ability to reorganize forces. This

reading needs to be harmonized with 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s statement that:

_“Now,when you behold in existence such organizations, arrangements and laws can you say that

all these are the effect of Nature, though Nature has neither intelligence nor perception?”_ [5]

On the other hand, one can argue that there is a qualitative threshold that natural description does

not fully capture: the emergence of reason introduces a mode of causation that cannot be reduced

to blind evolutionary processes. Either way, the examples converge on a single conclusion: the

distinctive human power is not lawbreaking but _lawful redirection_ , grounded in concepts,

reflection, and deliberate choice.

So 'Abdu'l-Bahá's language about man's relation to nature is not a call to marvel at outward

miracles performed by humans, but to contemplate the unique capacities of humans that

transcend nature. In the final analysis, an urgent corollary question remains: what will humanity

do with a consciousness that can bend the laws of nature toward ends of its own choosing?

- [1] SAQ page

- [2] PUP page

- [3] PUP page

- [4] PUP

- [5] SAQ page

Read in this light, the gist of 'Abdu'l-Bahá's claim is not that human beings cancel natural law,

but that a distinct mode of causation can arise: rational agency that understands, selects, and

reorganizes natural forces towards its needs. Ships, airplanes, submarines, and the Lunar Module

are not exceptions to nature; they are demonstrations of a new relation to nature, in which natural

limitations become usable conditions through knowledge and purposeful coordination. What is

"overcome" is not gravity or fluid dynamics themselves, but the artifact’s creator's prior

subjection to blind processes that program it to obey nature's constraints rather than go against

them. The philosophical principle presented is that "breaking" nature's laws reflects a shift in

capacity: the emergence of mind as a power that can redirect what blind process alone would

never intentionally assemble_._

**Conclusion: Emergence or Privilege?**

'Abdu'l-Bahá's claim that humanity can "break" and "subdue" nature invites a final question that

the examples in this paper have kept pressing from different angles: _can the human capacity to

redirect nature be fully explained as the output of natural processes, or does it signal a privilege

that is not explained by those processes?_

The airplane, the resilient mind, and the lunar trajectory do not suspend physics or override

causality. These scenarios succeed precisely because nature is stable, measurable, and

dependable. In that sense, "breaking" cannot mean cancellation of the natural law. It must mean a

change in relation to law, where constraints remain intact yet become usable through

understanding.

But this is where the philosophical dilemma returns. Nature can generate complexity and

behavior that appears goal-directed without explicit foresight. The more complex issue is

whether blind process can generate _law-interpreters and law-users,_ beings who can represent,

analyze constraints, compare alternatives, and deliberately organize means toward ends that

nature itself does not specify. The child thought experiment makes the point inwardly: if a person

were only a passive imprint of external forces, why would the person ever rise toward self-

revision at all? The lunar mission makes the point explicitly: if matter and life were evolving

only under local pressures and nature's influences, what accounts for the emergence of

conceptual planning, abstract reasoning, and the long discipline of experimentation that turns

gravity from a mighty barrier into a navigable scaffold?

Two broad readings are possible and should be reflected on. On one reading, rational agency is

an extraordinary but ultimately continuous outgrowth of natural history: evolution yields minds

that are capable of abstraction, and abstraction yields the ability to reorganize forces. This

reading needs to be harmonized with 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s statement that:

_“Now,when you behold in existence such organizations, arrangements and laws can you say that

all these are the effect of Nature, though Nature has neither intelligence nor perception?”_ [5]

On the other hand, one can argue that there is a qualitative threshold that natural description does

not fully capture: the emergence of reason introduces a mode of causation that cannot be reduced

to blind evolutionary processes. Either way, the examples converge on a single conclusion: the

distinctive human power is not lawbreaking but _lawful redirection_ , grounded in concepts,

reflection, and deliberate choice.

So 'Abdu'l-Bahá's language about man's relation to nature is not a call to marvel at outward

miracles performed by humans, but to contemplate the unique capacities of humans that

transcend nature. In the final analysis, an urgent corollary question remains: what will humanity

do with a consciousness that can bend the laws of nature toward ends of its own choosing?

- [1] SAQ page

- [2] PUP page

- [3] PUP page

- [4] PUP

- [5] SAQ page