Rethinking the Design Question: 'Abdu'l-Bahá's Revolutionary

# Synthesis of Design, Emergence, and Free Will

This essay examines Darwinian accounts and the modern Intelligent Design (ID) movement’s

approach to questions of intelligent causation and offers an interpretation of a Bahá’í-oriented

framework on the subject. It is intended as a starting point for inquiry, not a final or authoritative

treatment. Accordingly, the discussion is provisional: it sketches the conceptual terrain,

highlights promising lines of argument, and points to where later work can refine, revise, or

extend the approach.

This essay neither endorses the Intelligent Design Movement’s scientific, religious, or political

interpretations nor adopts its cultural or policy agendas

The analysis outline here reflects the author’s own interpretation and should not be taken as an

official Bahá’í position or as part of the authoritative Bahá’í writings.

## The Eternal Struggle to Discern Meaning in Randomness

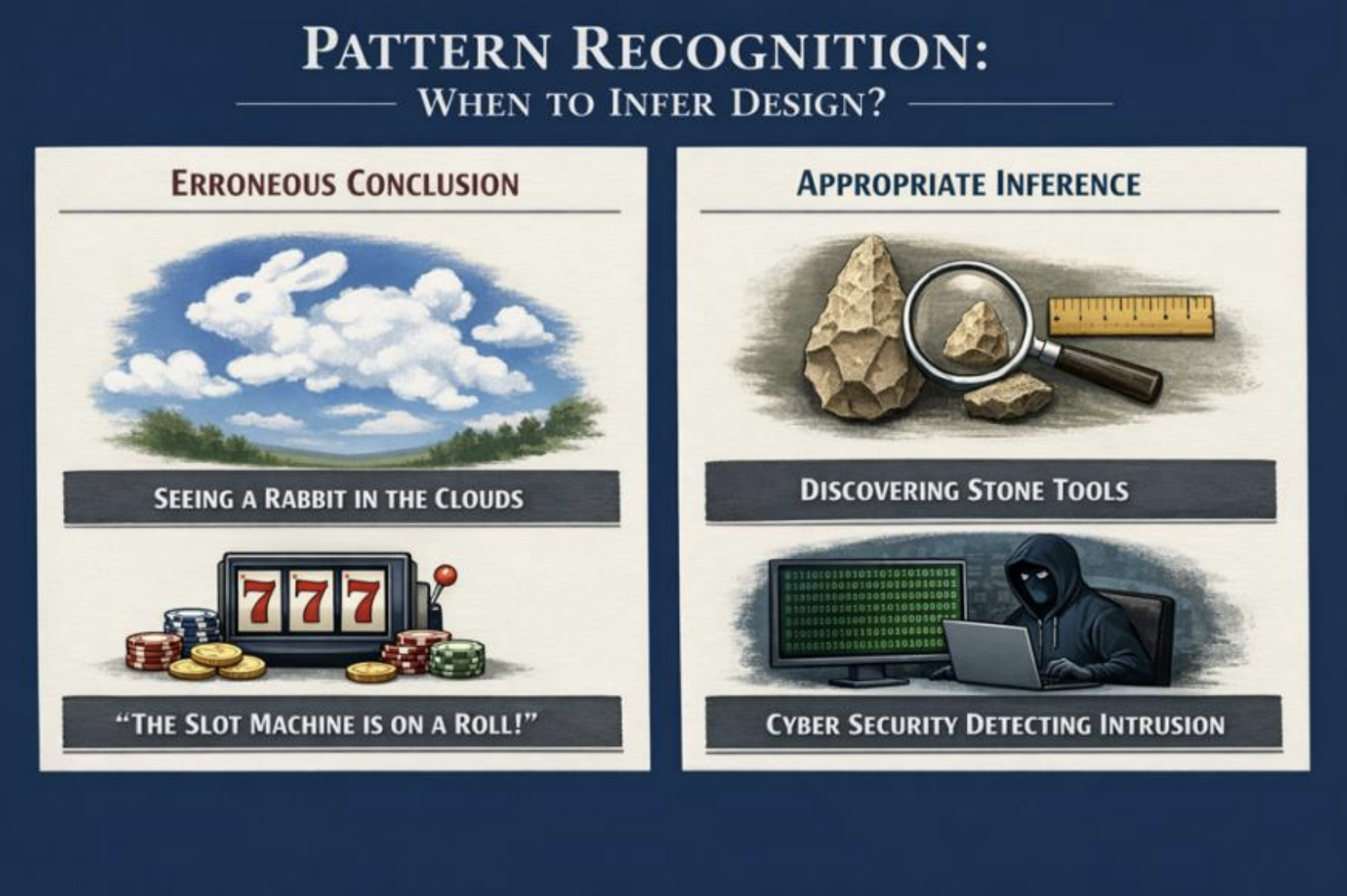

Human beings excel at finding patterns, inferring agency, and linking regularities to purposes.

We readily “see” faces in the Moon, animals in clouds, or profiles in wood grain, and hear

meaning in noise - radio static forming words or ambiguous voicemails sounding human after

repeated listening. We interpret chance as significant: hot hands in sports, lucky streaks at

roulette, or runs of correct guesses feel like evidence of special causation rather than ordinary

variance. Coincidences seem to be everywhere; matching shirts, recurring numbers, unlikely

meetings feel like it was fate.

Yet inferring design from patterns is often warranted and helpful: grammatical sentences, QR

codes, road signs, keys matching locks, or circuit board traces point to agency because we know

which processes reliably generate such structures.

This pattern-seeking logic drives efforts to detect extraterrestrial intelligence, searching for

engineered regularities rather than background noise, and cybersecurity intrusion detection,

which recognizes structured and repeated behaviors. Carl Sagan’s Contact captures the tension:

combing vast data streams for credible hallmarks of intelligence while resisting the impulse to

treat every anomaly as evidence of mind.

These cases show why teleological thinking resurfaces in debates about life’s functional order:

moving from patterned structure to purposive cause can be rational when constrained by

background knowledge, competing hypotheses, and tests separating genuine signature patterns

from regularities nature produces independently.

## Darwin’s Breakthrough: Rethinking Evolutionary Change and Adaptation

By the time Darwin penned his theory of evolution, European debates about order and design

had been reshaped by Enlightenment ideals of reason, public evidence, and intellectual

autonomy. Natural theology did not disappear, but it increasingly had to defend its claims in

broadly accessible terms rather than by appeal to ecclesial authority alone. This encouraged

discussions grounded in shared experience, empirical regularities, and the apparent intelligibility

of the world. At the same time, critiques of “occult” explanations and the growing prestige of

mechanistic, law-based accounts narrowed the space for explanations that relied directly on final

causes or special acts. Theology often responded by emphasizing a creator as legislator,

grounding the stability of natural laws, while treating design as readable in the general order of

nature rather than in ad hoc intervention.

Against that background, Darwin’s theory of natural selection altered the argumentative

landscape. Rather than denying that organisms look designed, Darwin offered a mechanism that

can generate adaptive fit without foresight. Variation, heritability, and differential reproductive

success produce cumulative change, and over long spans this can yield elaborate systems whose

parts appear coordinated for survival and reproduction. This shift matters epistemically because

it provides what design arguments often lacked: a detailed pathway from simpler antecedents to

complex outcomes, constrained by observable processes. Once such a pathway exists, the

inference from apparent design to an intelligent cause loses credibility. It becomes a comparative

question about explanatory performance, measured by evidential fit, breadth, and integration

with adjacent fields such as genetics, ecology, and developmental biology.

Richard Dawkins later crystallized this tension with his provocative phrase “the blind

watchmaker” stressing that natural selection can mimic the outputs of purposeful design without

being guided by intention; the phrase is contentious, but it marks a substantive claim that

evolutionary theory offers a non-intentional process with enough creative capacity, under

plausible conditions, to account for many appearances that earlier supported design inference.

The Darwinian Pathway to Complex Organization

Darwinian explanation begins from a simple premise: populations vary, some variation is

heritable, and organisms differ in reproductive success. From these elements, natural selection

follows as a cumulative filter, steadily increasing the frequency of traits that confer advantages in

particular environments. The process involves no foresight, yet it can yield remarkably

coordinated outcomes because each step is retained only insofar as it works locally. Selection is

therefore both constrained and opportunistic: constrained by available variation and by

developmental, physiological, and ecological limits, yet opportunistic in its ability to assemble

novelty from what already exists.

Complexity, in this view, is not a single property that arrives all at once; it is a historical product

of incremental modification, functional shifts, and the recombination of parts. Minor

improvements can accumulate into tightly integrated systems, while co-option can recruit traits

that originally served different roles. Gene duplication and divergence expand the search space

by freeing one copy to explore new functions. Over time, selection can deepen integration among

parts, transforming initially loose associations into interdependent networks.

A Darwinian account also benefits from distinguishing kinds of complexity that are often blurred

together. Structural complexity can mean mere intricacy, many parts and interactions, without

implying purposeful organization. Functional complexity refers to reliable performance, in which

components are organized to carry out a task consistently despite ordinary randomness and

perturbations. Evolutionary theory expects both, but it treats functional organization as especially

likely where selection repeatedly rewards performance and stabilizes improvements, which helps

explain why living systems often display regulation, redundancy, error correction, and adaptive

responsiveness. Such features can sound “engineered” in ordinary speech, yet they are also the

sort of properties that selection tends to preserve when reliability is advantageous.

## Modern Intelligent Design Movement and Its Core Claims

Emerging in the late twentieth century, the modern Intelligent Design (ID) movement represents

a strategic effort to reframe design reasoning as an evidentiary inference rather than a theological

deduction. Unlike earlier teleological arguments or natural theology, which often operated as

metaphysical commentaries on nature, modern ID aims to establish ‘design’ as an empirically

detectable feature of the physical world.

The movement’s core premise is that recognizing intelligence is already a standard scientific

practice in fields such as forensics, cryptography, and SETI. Proponents argue that biology

should be subject to the same explanatory filter used in these domains, which distinguishes

between effects caused by natural laws, random chance, and directed agency. By applying this

filter to biological systems, ID proponents contend that the third category, intelligent causation,

best explains certain features. Crucially, by treating the designer as an abstract agent and setting

aside questions of religious identity, the movement seeks to shift the controversy from the

identity of the cause to the detectability of the effect.

The movement’s ideology centers on the concept of information as a distinct ontological category

that cannot be reduced to matter or energy. The basic framework asserts that functional complex

systems possess a quality that natural selection cannot mimic. This is codified in two primary

arguments:

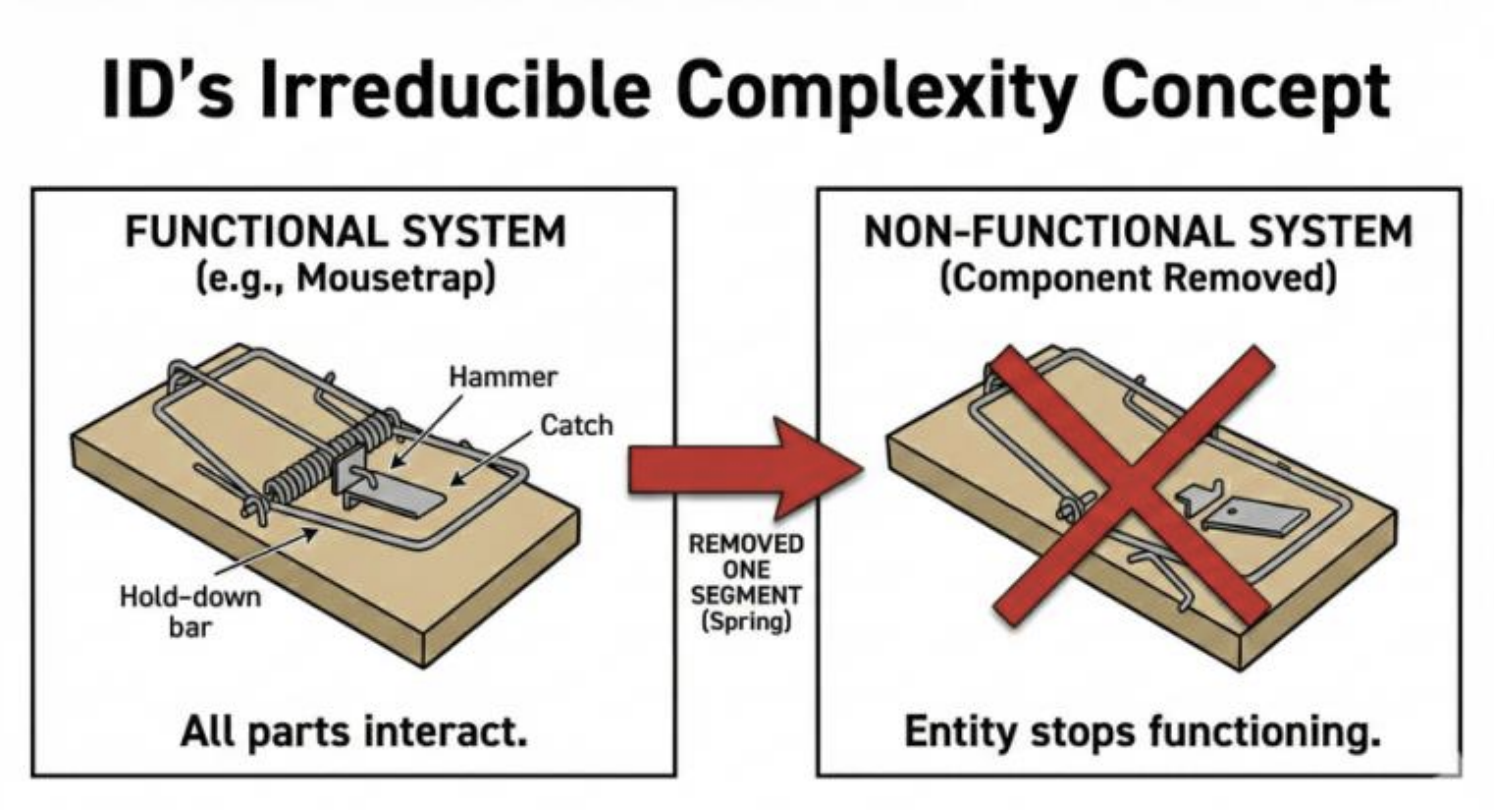

Irreducible Complexity: This biological argument states that certain molecular formations consist

of multiple, interacting parts, all of which are necessary for the function to exist. A system is said

to be irreducibly complex if it consists of numerous well-matched interacting parts that jointly

perform a basic function, such that removing any key part causes loss of that function. The

intended inference is historical: because the system requires all its parts to perform its current

function, a gradual evolutionary pathway is unlikely, since intermediate stages would be non-

functional and therefore would not confer a selectable advantage for natural selection to

preserve.

These cases show why teleological thinking resurfaces in debates about life’s functional order:

moving from patterned structure to purposive cause can be rational when constrained by

background knowledge, competing hypotheses, and tests separating genuine signature patterns

from regularities nature produces independently.

## Darwin’s Breakthrough: Rethinking Evolutionary Change and Adaptation

By the time Darwin penned his theory of evolution, European debates about order and design

had been reshaped by Enlightenment ideals of reason, public evidence, and intellectual

autonomy. Natural theology did not disappear, but it increasingly had to defend its claims in

broadly accessible terms rather than by appeal to ecclesial authority alone. This encouraged

discussions grounded in shared experience, empirical regularities, and the apparent intelligibility

of the world. At the same time, critiques of “occult” explanations and the growing prestige of

mechanistic, law-based accounts narrowed the space for explanations that relied directly on final

causes or special acts. Theology often responded by emphasizing a creator as legislator,

grounding the stability of natural laws, while treating design as readable in the general order of

nature rather than in ad hoc intervention.

Against that background, Darwin’s theory of natural selection altered the argumentative

landscape. Rather than denying that organisms look designed, Darwin offered a mechanism that

can generate adaptive fit without foresight. Variation, heritability, and differential reproductive

success produce cumulative change, and over long spans this can yield elaborate systems whose

parts appear coordinated for survival and reproduction. This shift matters epistemically because

it provides what design arguments often lacked: a detailed pathway from simpler antecedents to

complex outcomes, constrained by observable processes. Once such a pathway exists, the

inference from apparent design to an intelligent cause loses credibility. It becomes a comparative

question about explanatory performance, measured by evidential fit, breadth, and integration

with adjacent fields such as genetics, ecology, and developmental biology.

Richard Dawkins later crystallized this tension with his provocative phrase “the blind

watchmaker” stressing that natural selection can mimic the outputs of purposeful design without

being guided by intention; the phrase is contentious, but it marks a substantive claim that

evolutionary theory offers a non-intentional process with enough creative capacity, under

plausible conditions, to account for many appearances that earlier supported design inference.

The Darwinian Pathway to Complex Organization

Darwinian explanation begins from a simple premise: populations vary, some variation is

heritable, and organisms differ in reproductive success. From these elements, natural selection

follows as a cumulative filter, steadily increasing the frequency of traits that confer advantages in

particular environments. The process involves no foresight, yet it can yield remarkably

coordinated outcomes because each step is retained only insofar as it works locally. Selection is

therefore both constrained and opportunistic: constrained by available variation and by

developmental, physiological, and ecological limits, yet opportunistic in its ability to assemble

novelty from what already exists.

Complexity, in this view, is not a single property that arrives all at once; it is a historical product

of incremental modification, functional shifts, and the recombination of parts. Minor

improvements can accumulate into tightly integrated systems, while co-option can recruit traits

that originally served different roles. Gene duplication and divergence expand the search space

by freeing one copy to explore new functions. Over time, selection can deepen integration among

parts, transforming initially loose associations into interdependent networks.

A Darwinian account also benefits from distinguishing kinds of complexity that are often blurred

together. Structural complexity can mean mere intricacy, many parts and interactions, without

implying purposeful organization. Functional complexity refers to reliable performance, in which

components are organized to carry out a task consistently despite ordinary randomness and

perturbations. Evolutionary theory expects both, but it treats functional organization as especially

likely where selection repeatedly rewards performance and stabilizes improvements, which helps

explain why living systems often display regulation, redundancy, error correction, and adaptive

responsiveness. Such features can sound “engineered” in ordinary speech, yet they are also the

sort of properties that selection tends to preserve when reliability is advantageous.

## Modern Intelligent Design Movement and Its Core Claims

Emerging in the late twentieth century, the modern Intelligent Design (ID) movement represents

a strategic effort to reframe design reasoning as an evidentiary inference rather than a theological

deduction. Unlike earlier teleological arguments or natural theology, which often operated as

metaphysical commentaries on nature, modern ID aims to establish ‘design’ as an empirically

detectable feature of the physical world.

The movement’s core premise is that recognizing intelligence is already a standard scientific

practice in fields such as forensics, cryptography, and SETI. Proponents argue that biology

should be subject to the same explanatory filter used in these domains, which distinguishes

between effects caused by natural laws, random chance, and directed agency. By applying this

filter to biological systems, ID proponents contend that the third category, intelligent causation,

best explains certain features. Crucially, by treating the designer as an abstract agent and setting

aside questions of religious identity, the movement seeks to shift the controversy from the

identity of the cause to the detectability of the effect.

The movement’s ideology centers on the concept of information as a distinct ontological category

that cannot be reduced to matter or energy. The basic framework asserts that functional complex

systems possess a quality that natural selection cannot mimic. This is codified in two primary

arguments:

Irreducible Complexity: This biological argument states that certain molecular formations consist

of multiple, interacting parts, all of which are necessary for the function to exist. A system is said

to be irreducibly complex if it consists of numerous well-matched interacting parts that jointly

perform a basic function, such that removing any key part causes loss of that function. The

intended inference is historical: because the system requires all its parts to perform its current

function, a gradual evolutionary pathway is unlikely, since intermediate stages would be non-

functional and therefore would not confer a selectable advantage for natural selection to

preserve.

Intelligent Design proponents illustrate irreducible complexity with a mousetrap, which requires

five components - base plate, spring, hammer, holding bar, and catch - arranged such that

removing any single part renders it non-functional. Applied to biology, the argument claims that

evolutionary precursors to such systems would be non-functional and therefore could not have

been favored by natural selection. However, critics often point out that a system lacking one

component, while unable to perform its current function, may still perform a different, simpler

function that could have been advantageous to ancestors, making it a viable evolutionary

precursor.

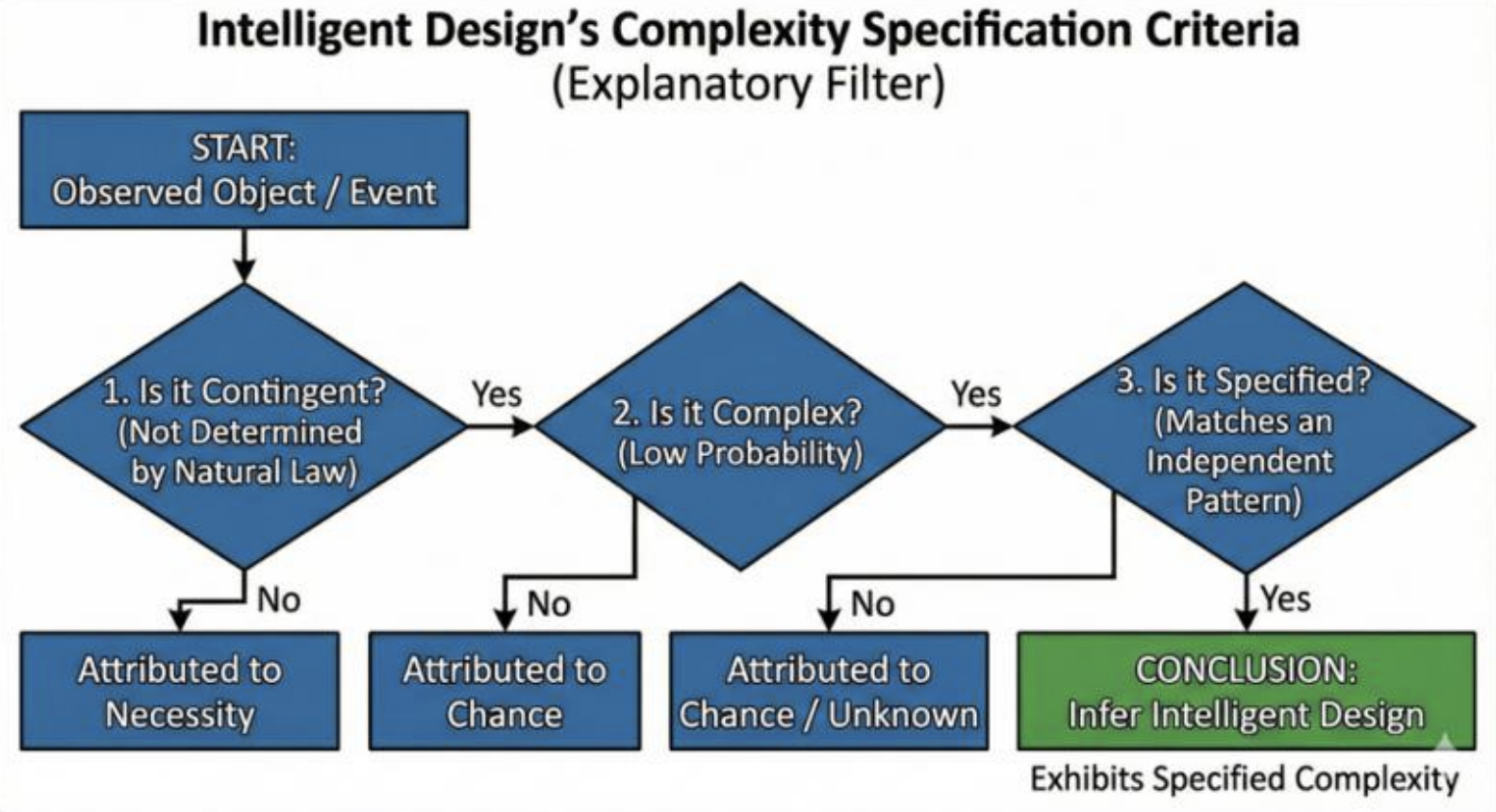

Specified Complexity: Specified Complexity Information (CSI) is a mathematical framework that

aims to detect design by combining low probability with an independently defined pattern. Since

many outcomes are unlikely without implying agency, CSI argues that design is supported only

when an outcome is both highly improbable under a relevant chance hypothesis and “specified,”

meaning it matches a pattern set independently of the result. This specification requirement is

intended to prevent picking the target after seeing the data, which can make almost any outcome

look significant. In the explanatory filter, the inference proceeds in steps: determine whether the

event is contingent rather than necessary, whether it exceeds a complexity threshold, and

whether it is independently specified; only then does the filter yield design rather than necessity

or chance.

Intelligent Design proponents illustrate irreducible complexity with a mousetrap, which requires

five components - base plate, spring, hammer, holding bar, and catch - arranged such that

removing any single part renders it non-functional. Applied to biology, the argument claims that

evolutionary precursors to such systems would be non-functional and therefore could not have

been favored by natural selection. However, critics often point out that a system lacking one

component, while unable to perform its current function, may still perform a different, simpler

function that could have been advantageous to ancestors, making it a viable evolutionary

precursor.

Specified Complexity: Specified Complexity Information (CSI) is a mathematical framework that

aims to detect design by combining low probability with an independently defined pattern. Since

many outcomes are unlikely without implying agency, CSI argues that design is supported only

when an outcome is both highly improbable under a relevant chance hypothesis and “specified,”

meaning it matches a pattern set independently of the result. This specification requirement is

intended to prevent picking the target after seeing the data, which can make almost any outcome

look significant. In the explanatory filter, the inference proceeds in steps: determine whether the

event is contingent rather than necessary, whether it exceeds a complexity threshold, and

whether it is independently specified; only then does the filter yield design rather than necessity

or chance.

A concrete illustration of complex specified information comes from cybersecurity incident

response. Suppose monitoring captures two equal-length network payload strings: one is high-

entropy noise consistent with compressed traffic; the other contains structured patterns matching

a known command-and-control beacon format from prior threat reports. Both strings are highly

improbable, so rarity alone doesn’t distinguish benign from malicious. CSI reasoning depends on

specification: the suspicious string matches an independently defined pattern class, described

before capture, and compactly expressible. Given realistic generative models, malware produces

such beacons while random traffic is unlikely to. Evidential force lies in this conjunction, not

rarity alone.

Challenging Methodological Naturalism: A central feature of science is methodological

naturalism, explaining natural phenomena through publicly testable causes. Intelligent Design

challenges this principle, arguing that restricting explanations to material causes arbitrarily

excludes intelligent causation. ID theorists contend that methodological naturalism functions as

dogma rather than justified methodology, and they seek to expand scientific explanation to

include non-material agency. Thus, ID represents not merely a dispute about biological

mechanisms, but a fundamental disagreement about the epistemic rules governing explanations

of complex origins.

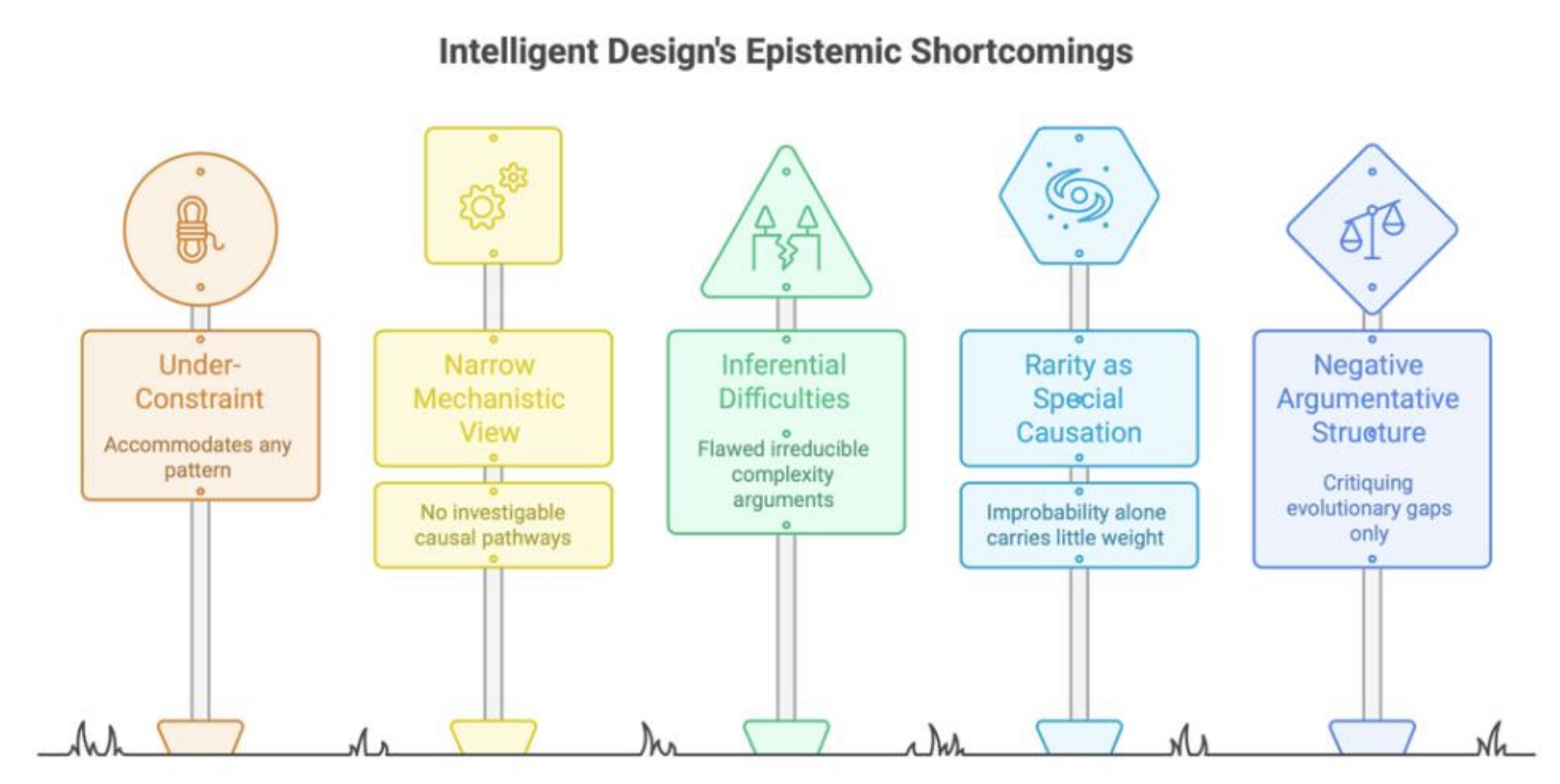

Where Intelligent Design Falls Short

Most philosophers of science and biologists reject Intelligent Design not for logical incoherence,

but for lacking the epistemic virtues of productive scientific explanations. Successful hypotheses

constrain outcomes, specify testable mechanisms, and generate falsifiable predictions. Intelligent

Design suffers from under-constraint: claiming “an intelligent cause produced this”

accommodates virtually any biological pattern without identifying the designer’s capacities,

constraints, or empirical signatures. Such broad compatibility prevents meaningful

discrimination from competing explanations.

A second weakness is a narrow mechanistic view of evolution. Evolutionary theory offers

extensive testable mechanisms: natural selection, drift, duplication, co-option, and

developmental constraint; integrating coherently across biological levels. ID arguments typically

stop at attributing design without elaborating investigable causal pathways. While stimulating

debate, Intelligent Design has produced few distinctive research trajectories that have yielded

empirical discoveries attributable to design rather than evolutionary processes.

Intelligent Design’s signature concepts face inferential difficulties. Irreducible complexity

arguments infer historical impossibility from present functional features. Yet, critics note that

evolutionary pathways operate through functional shifts, redundancy, scaffolding, and co-option,

allowing selectable intermediates that don’t perform the final function. Complex specified

information arguments depend on independent specification and realistic alternative models, but

often fail on both counts. Intuitions about probability usually err when evolution is misconceived

as purely random sampling, leading to complex outcomes being deemed astronomically unlikely.

This misses the Darwinian point: natural selection is a non-random filter that retains beneficial

traits and eliminates deleterious ones. The epistemic question shifts from computing the one-step

assembly probability to assessing whether credible stepwise routes exist in which intermediates

function adequately.

A related shortcoming is treating rarity as evidence of special causation. Any particular sequence

is exceedingly improbable beforehand, so rarity alone carries little weight. When “chance

hypotheses” misconstrue evolution as random sampling or specifications are determined post

hoc, probability calculations mislead rather than compare realistic causal models. Defensible

design inference requires independently specified patterns, not mere improbability. Evolutionary

inquiry, therefore, reconstructs mechanisms and pathways, seeking signatures of incremental

adaptation: trade-offs, constraints, vestigial features, and imperfect solutions that mark

selection’s cumulative work.

Intelligent Design’s argumentative structure operates largely negatively, critiquing evolutionary

gaps. But identifying one framework’s incompleteness doesn’t establish an alternative.

Competing hypotheses require independent evidential support and predictive leverage. Without

this, “design” becomes a retreating placeholder, explaining why critics deem the Intelligent

Design methodologically unproductive.

A concrete illustration of complex specified information comes from cybersecurity incident

response. Suppose monitoring captures two equal-length network payload strings: one is high-

entropy noise consistent with compressed traffic; the other contains structured patterns matching

a known command-and-control beacon format from prior threat reports. Both strings are highly

improbable, so rarity alone doesn’t distinguish benign from malicious. CSI reasoning depends on

specification: the suspicious string matches an independently defined pattern class, described

before capture, and compactly expressible. Given realistic generative models, malware produces

such beacons while random traffic is unlikely to. Evidential force lies in this conjunction, not

rarity alone.

Challenging Methodological Naturalism: A central feature of science is methodological

naturalism, explaining natural phenomena through publicly testable causes. Intelligent Design

challenges this principle, arguing that restricting explanations to material causes arbitrarily

excludes intelligent causation. ID theorists contend that methodological naturalism functions as

dogma rather than justified methodology, and they seek to expand scientific explanation to

include non-material agency. Thus, ID represents not merely a dispute about biological

mechanisms, but a fundamental disagreement about the epistemic rules governing explanations

of complex origins.

Where Intelligent Design Falls Short

Most philosophers of science and biologists reject Intelligent Design not for logical incoherence,

but for lacking the epistemic virtues of productive scientific explanations. Successful hypotheses

constrain outcomes, specify testable mechanisms, and generate falsifiable predictions. Intelligent

Design suffers from under-constraint: claiming “an intelligent cause produced this”

accommodates virtually any biological pattern without identifying the designer’s capacities,

constraints, or empirical signatures. Such broad compatibility prevents meaningful

discrimination from competing explanations.

A second weakness is a narrow mechanistic view of evolution. Evolutionary theory offers

extensive testable mechanisms: natural selection, drift, duplication, co-option, and

developmental constraint; integrating coherently across biological levels. ID arguments typically

stop at attributing design without elaborating investigable causal pathways. While stimulating

debate, Intelligent Design has produced few distinctive research trajectories that have yielded

empirical discoveries attributable to design rather than evolutionary processes.

Intelligent Design’s signature concepts face inferential difficulties. Irreducible complexity

arguments infer historical impossibility from present functional features. Yet, critics note that

evolutionary pathways operate through functional shifts, redundancy, scaffolding, and co-option,

allowing selectable intermediates that don’t perform the final function. Complex specified

information arguments depend on independent specification and realistic alternative models, but

often fail on both counts. Intuitions about probability usually err when evolution is misconceived

as purely random sampling, leading to complex outcomes being deemed astronomically unlikely.

This misses the Darwinian point: natural selection is a non-random filter that retains beneficial

traits and eliminates deleterious ones. The epistemic question shifts from computing the one-step

assembly probability to assessing whether credible stepwise routes exist in which intermediates

function adequately.

A related shortcoming is treating rarity as evidence of special causation. Any particular sequence

is exceedingly improbable beforehand, so rarity alone carries little weight. When “chance

hypotheses” misconstrue evolution as random sampling or specifications are determined post

hoc, probability calculations mislead rather than compare realistic causal models. Defensible

design inference requires independently specified patterns, not mere improbability. Evolutionary

inquiry, therefore, reconstructs mechanisms and pathways, seeking signatures of incremental

adaptation: trade-offs, constraints, vestigial features, and imperfect solutions that mark

selection’s cumulative work.

Intelligent Design’s argumentative structure operates largely negatively, critiquing evolutionary

gaps. But identifying one framework’s incompleteness doesn’t establish an alternative.

Competing hypotheses require independent evidential support and predictive leverage. Without

this, “design” becomes a retreating placeholder, explaining why critics deem the Intelligent

Design methodologically unproductive.

## ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and the Reframing of Design, Complexity, and Free Will

Across his talks, tablets, and correspondence, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá repeatedly engages questions central

to contemporary intelligent design debates, addressing purposiveness in nature, the emergence of

organized complexity, and human volition. Remarkably, several ideas that later became

foundational to the Intelligent Design Movement appear in his discourse many decades before.

This essay does not claim a one-to-one correspondence between ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and contemporary

ID frameworks; its aim is strictly analytic, identifying possible points of conceptual convergence

and examining their implications.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Design Decision Criteria

At the heart of Intelligent Design’s complexity-specification criteria lies a procedure addressing

three fundamental questions: should we attribute an event or the formation of an entity to

necessity , chance, or design? ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, in his tablet to August Forel, has indicated a similar

decision criterion.

“Now, formation is of three kinds and of three kinds only: accidental, necessary and voluntary.

The coming together of the various constituent elements of beings cannot be accidental, for unto

every effect there must be a cause. It cannot be compulsory, for then the formation must be an

inherent property of the constituent parts and the inherent property of a thing can in no wise be

dissociated from it..Thus under such circumstances the decomposition of any formation is

impossible, for the inherent properties of a thing cannot be separated from it. The third

formation remaineth and that is the voluntary one, that is, an unseen force described as the

Ancient Power, causeth these elements to come together, every formation giving rise to a distinct

being.” [1]

The core claim of irreducible complexity in ID is that some systems consist of multiple, tightly

coordinated, interacting parts that jointly enable a basic function, such that removing any one

part causes the system to lose that function. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá has reiterated this concept decades

before.

“For instance, as we have observed, co-operation among the constituent parts of the human body

is clearly established, and these parts and members render services unto all the component parts

of the body.. Likewise every arrangement and formation that is not perfect in its order we

designate as accidental, and that which is orderly, regular, perfect in its relations and every part

of which is in its proper place and is the essential requisite of the other constituent parts, this we

call a composition formed through will and knowledge.” [2]

The apparent overlap between ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s statements and key themes in the Intelligent

Design framework raises a critical question:

Does the Bahá’í approach offer a genuinely distinctive account of design, or does it inherit the

same conceptual and philosophical weaknesses often attributed to the Intelligent Design

movement?

Bahá’í Paradigm Shift: Behavior Trumps Structure

The distinction of the Bahá’í approach lies in a crucial additional component that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá

consistently emphasizes. Integrating this element fundamentally transforms ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s

treatment of design, complexity, and free will into a distinctive philosophical framework that

addresses many of the criticisms of the Intelligent Design movement.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Tablet to Auguste Forel offers a clear window into his reasoning about intelligent

causation. Before engaging themes that resemble irreducible complexity or other design-oriented

ideas, he begins from a radically different starting point: humanity’s distinctive manner of

interacting with nature. He offers concrete examples to show that the human intellect does not

merely submit to natural forces but can discover their regularities and deliberately redirect them

toward chosen ends.

“Consider: according to the law of nature man liveth, moveth and hath his being on earth, yet his

soul and mind interfere with the laws thereof, and even as the bird he flieth in the air, saileth

speedily upon the seas and as the fish soundeth the deep and discovereth the things therein.

Verily this is a grievous defeat inflicted upon the laws of nature.” [3]

This starting line of argument reframes what “design” is taken to mean. Instead of drawing a

verdict solely from the arrangement of parts in a finished structure, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá adds a second

dimension centered on what an entity can do relative to nature’s constraints. Alongside a

configuration-based analysis of organized forms, he introduces a behavior-based component that

emphasizes capacities, agency, and modes of lawful interaction. The implications are substantial:

the focus shifts from static features to dynamic powers and patterns of action, and the evidential

standard becomes more observer-independent. Because the laws of nature are taken to be

invariant across the universe, modes of interaction with those laws supply a universal reference

point that, in principle, any competent observer, anywhere, could recognize and assess.

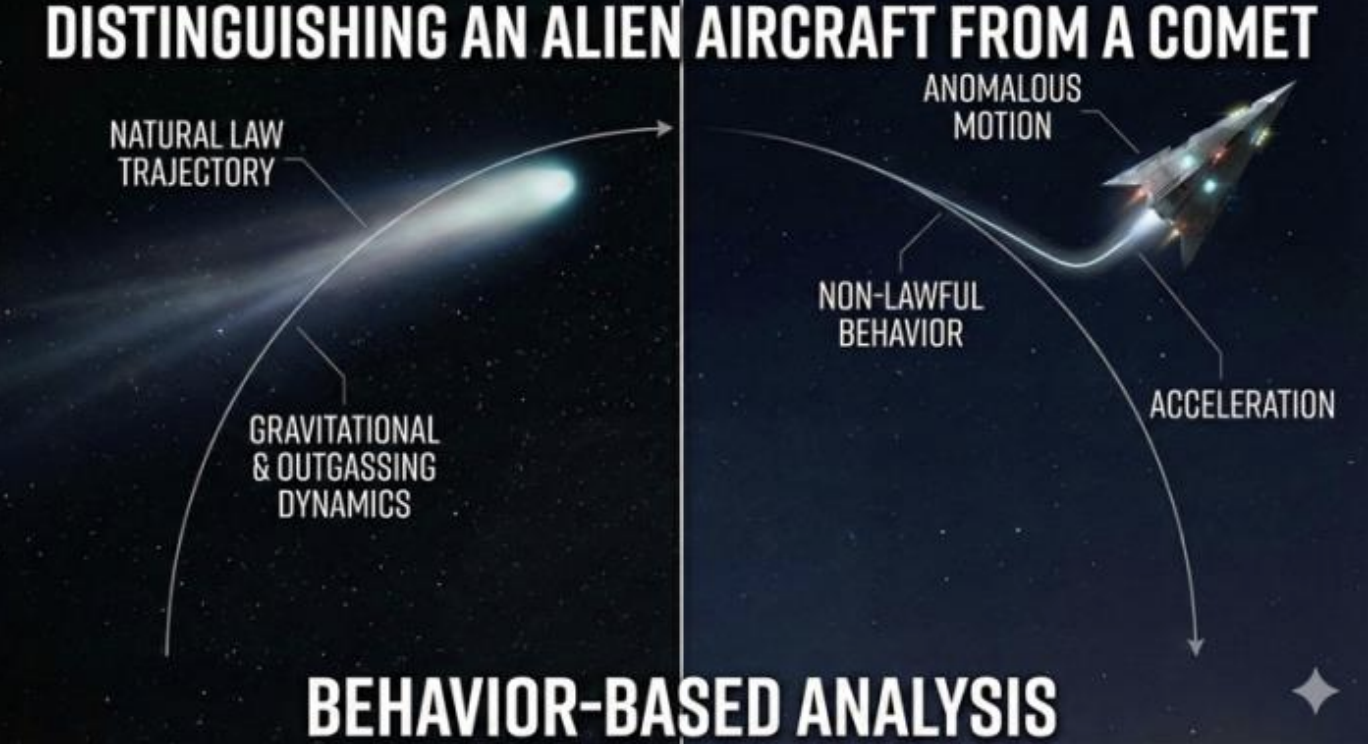

Astronomy offers a helpful analogy. To distinguish an alien craft from a comet, composition

alone may be unclear; what matters is behavior under natural law. Astronomers examine

trajectories and accelerations to see whether motion matches gravity and typical outgassing.

Because these regularities supply a shared reference for any observer, anomaly detection often

prioritizes law-governed behavior over structural description.

## ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and the Reframing of Design, Complexity, and Free Will

Across his talks, tablets, and correspondence, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá repeatedly engages questions central

to contemporary intelligent design debates, addressing purposiveness in nature, the emergence of

organized complexity, and human volition. Remarkably, several ideas that later became

foundational to the Intelligent Design Movement appear in his discourse many decades before.

This essay does not claim a one-to-one correspondence between ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and contemporary

ID frameworks; its aim is strictly analytic, identifying possible points of conceptual convergence

and examining their implications.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Design Decision Criteria

At the heart of Intelligent Design’s complexity-specification criteria lies a procedure addressing

three fundamental questions: should we attribute an event or the formation of an entity to

necessity , chance, or design? ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, in his tablet to August Forel, has indicated a similar

decision criterion.

“Now, formation is of three kinds and of three kinds only: accidental, necessary and voluntary.

The coming together of the various constituent elements of beings cannot be accidental, for unto

every effect there must be a cause. It cannot be compulsory, for then the formation must be an

inherent property of the constituent parts and the inherent property of a thing can in no wise be

dissociated from it..Thus under such circumstances the decomposition of any formation is

impossible, for the inherent properties of a thing cannot be separated from it. The third

formation remaineth and that is the voluntary one, that is, an unseen force described as the

Ancient Power, causeth these elements to come together, every formation giving rise to a distinct

being.” [1]

The core claim of irreducible complexity in ID is that some systems consist of multiple, tightly

coordinated, interacting parts that jointly enable a basic function, such that removing any one

part causes the system to lose that function. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá has reiterated this concept decades

before.

“For instance, as we have observed, co-operation among the constituent parts of the human body

is clearly established, and these parts and members render services unto all the component parts

of the body.. Likewise every arrangement and formation that is not perfect in its order we

designate as accidental, and that which is orderly, regular, perfect in its relations and every part

of which is in its proper place and is the essential requisite of the other constituent parts, this we

call a composition formed through will and knowledge.” [2]

The apparent overlap between ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s statements and key themes in the Intelligent

Design framework raises a critical question:

Does the Bahá’í approach offer a genuinely distinctive account of design, or does it inherit the

same conceptual and philosophical weaknesses often attributed to the Intelligent Design

movement?

Bahá’í Paradigm Shift: Behavior Trumps Structure

The distinction of the Bahá’í approach lies in a crucial additional component that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá

consistently emphasizes. Integrating this element fundamentally transforms ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s

treatment of design, complexity, and free will into a distinctive philosophical framework that

addresses many of the criticisms of the Intelligent Design movement.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Tablet to Auguste Forel offers a clear window into his reasoning about intelligent

causation. Before engaging themes that resemble irreducible complexity or other design-oriented

ideas, he begins from a radically different starting point: humanity’s distinctive manner of

interacting with nature. He offers concrete examples to show that the human intellect does not

merely submit to natural forces but can discover their regularities and deliberately redirect them

toward chosen ends.

“Consider: according to the law of nature man liveth, moveth and hath his being on earth, yet his

soul and mind interfere with the laws thereof, and even as the bird he flieth in the air, saileth

speedily upon the seas and as the fish soundeth the deep and discovereth the things therein.

Verily this is a grievous defeat inflicted upon the laws of nature.” [3]

This starting line of argument reframes what “design” is taken to mean. Instead of drawing a

verdict solely from the arrangement of parts in a finished structure, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá adds a second

dimension centered on what an entity can do relative to nature’s constraints. Alongside a

configuration-based analysis of organized forms, he introduces a behavior-based component that

emphasizes capacities, agency, and modes of lawful interaction. The implications are substantial:

the focus shifts from static features to dynamic powers and patterns of action, and the evidential

standard becomes more observer-independent. Because the laws of nature are taken to be

invariant across the universe, modes of interaction with those laws supply a universal reference

point that, in principle, any competent observer, anywhere, could recognize and assess.

Astronomy offers a helpful analogy. To distinguish an alien craft from a comet, composition

alone may be unclear; what matters is behavior under natural law. Astronomers examine

trajectories and accelerations to see whether motion matches gravity and typical outgassing.

Because these regularities supply a shared reference for any observer, anomaly detection often

prioritizes law-governed behavior over structural description.

The Intelligent Design movement, by contrast, tends to concentrate on the arrangement and

coordination of molecular components and organismal structures, for example, pointing to

intricate biochemical machinery or the tightly coupled organization found across diverse life

forms. By contrast, Darwinian theory largely explains how natural selection and other natural

laws shape organisms over time. Still, it offers a thinner account of how the organism, once

formed, can actively engage, harness, or redirect those same laws in its own behavior.

Measuring Complexity by Interaction, Not Intricacy

Intelligent Design discussions often treat “complexity” and “function” as if their meaning were

self-evident, yet the criteria are frequently underspecified. A structure is labeled complex

because it looks intricate, and it is labeled functional because it appears to serve a purpose. This

approach is vulnerable to after-the-fact selection: once an outcome exists, observers can

highlight whichever features make it seem special, then infer significance from the highlighted

pattern. The problem is not that biological systems lack organization, but that the boundary

between “meaningful organization” and “mere arrangement” can shift with the observer’s

background assumptions.

This observer-dependence becomes clearer under a simple thought experiment. A biological

configuration that humans interpret as exquisitely coordinated might not register as “functionally

organized” to an extraterrestrial whose embodiment, sensory access, and biological architecture

differ radically from ours. If the alien’s categories of function are keyed to entirely different

substrates and constraints, many of our “salient” biological patterns could appear arbitrary or

even unintelligible. In that case, the inference is not tracking a foundational property of the

system alone, but a match between the system and the observer’s prior conceptual scheme.

Darwinian theory offers a more disciplined route for classifying function because it ties it to a

universal, testable criterion: differential contribution to survival and reproduction under specific

conditions. A trait’s function is not whatever an observer finds impressive; it is what the trait

does that selection can preserve, refine, or repurpose across generations. Complexity, in this

framework, is often described as the cumulative integration of multiple parts and processes

shaped by selection through gradual modification, co-option, and increasing interdependence.

Yet “complexity” remains vague and less tightly fixed than “function”: it can refer to the number

of parts, degree of interdependence, informational structure, or the length of an evolutionary

pathway, and these measures do not always align consistently.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá introduces an additional way to classify complexity that shifts attention from static

configuration to interaction with nature’s laws. In this narrative, the most important feature is not

only how parts are arranged, but how an entity can recognize, engage, and redirect regularities in

nature toward chosen ends. This behavior-centered criterion has a distinctive advantage: it leans

on the assumed universality of natural law. If the laws of nature are invariant for any competent

observer, then the capacity to understand and harness those laws offers a more observer-

independent reference point than judging what “looks designed” on structural grounds alone. In

that sense, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s framework proposes a generalizable, universally agreed upon measure

of complexity grounded in lawful constraint and responsive engagement with nature’s laws.

The Intelligent Design movement, by contrast, tends to concentrate on the arrangement and

coordination of molecular components and organismal structures, for example, pointing to

intricate biochemical machinery or the tightly coupled organization found across diverse life

forms. By contrast, Darwinian theory largely explains how natural selection and other natural

laws shape organisms over time. Still, it offers a thinner account of how the organism, once

formed, can actively engage, harness, or redirect those same laws in its own behavior.

Measuring Complexity by Interaction, Not Intricacy

Intelligent Design discussions often treat “complexity” and “function” as if their meaning were

self-evident, yet the criteria are frequently underspecified. A structure is labeled complex

because it looks intricate, and it is labeled functional because it appears to serve a purpose. This

approach is vulnerable to after-the-fact selection: once an outcome exists, observers can

highlight whichever features make it seem special, then infer significance from the highlighted

pattern. The problem is not that biological systems lack organization, but that the boundary

between “meaningful organization” and “mere arrangement” can shift with the observer’s

background assumptions.

This observer-dependence becomes clearer under a simple thought experiment. A biological

configuration that humans interpret as exquisitely coordinated might not register as “functionally

organized” to an extraterrestrial whose embodiment, sensory access, and biological architecture

differ radically from ours. If the alien’s categories of function are keyed to entirely different

substrates and constraints, many of our “salient” biological patterns could appear arbitrary or

even unintelligible. In that case, the inference is not tracking a foundational property of the

system alone, but a match between the system and the observer’s prior conceptual scheme.

Darwinian theory offers a more disciplined route for classifying function because it ties it to a

universal, testable criterion: differential contribution to survival and reproduction under specific

conditions. A trait’s function is not whatever an observer finds impressive; it is what the trait

does that selection can preserve, refine, or repurpose across generations. Complexity, in this

framework, is often described as the cumulative integration of multiple parts and processes

shaped by selection through gradual modification, co-option, and increasing interdependence.

Yet “complexity” remains vague and less tightly fixed than “function”: it can refer to the number

of parts, degree of interdependence, informational structure, or the length of an evolutionary

pathway, and these measures do not always align consistently.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá introduces an additional way to classify complexity that shifts attention from static

configuration to interaction with nature’s laws. In this narrative, the most important feature is not

only how parts are arranged, but how an entity can recognize, engage, and redirect regularities in

nature toward chosen ends. This behavior-centered criterion has a distinctive advantage: it leans

on the assumed universality of natural law. If the laws of nature are invariant for any competent

observer, then the capacity to understand and harness those laws offers a more observer-

independent reference point than judging what “looks designed” on structural grounds alone. In

that sense, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s framework proposes a generalizable, universally agreed upon measure

of complexity grounded in lawful constraint and responsive engagement with nature’s laws.

Hierarchical Complexity

A recurring limitation in both the Intelligent Design (ID) literature and standard Darwinian

presentations is that neither offers a fundamental, widely accepted way to sort “complexity” into

discrete hierarchical levels. ID typically treats complexity as a marker that triggers design

inference, but its criteria do not naturally yield a principled taxonomy of kinds or grades of

complexity. Darwinian accounts explain how complexity can accumulate historically, yet they

often treat “complexity” as a family of measures rather than a well-defined set of categories. By

contrast, the Bahá’í framework interpreted here offers a consistent basis for hierarchical

classification by grounding complexity in law-interaction capacities.

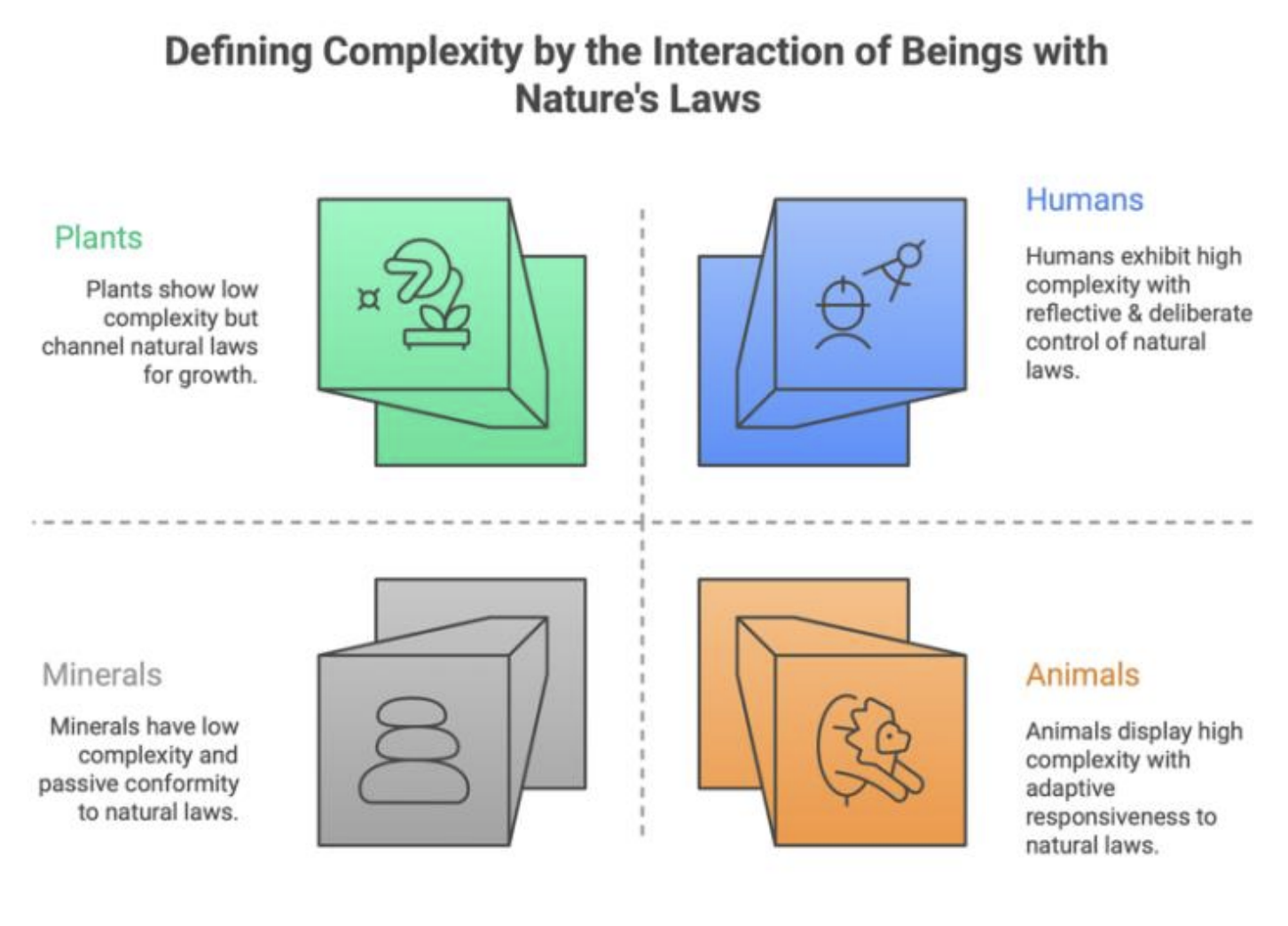

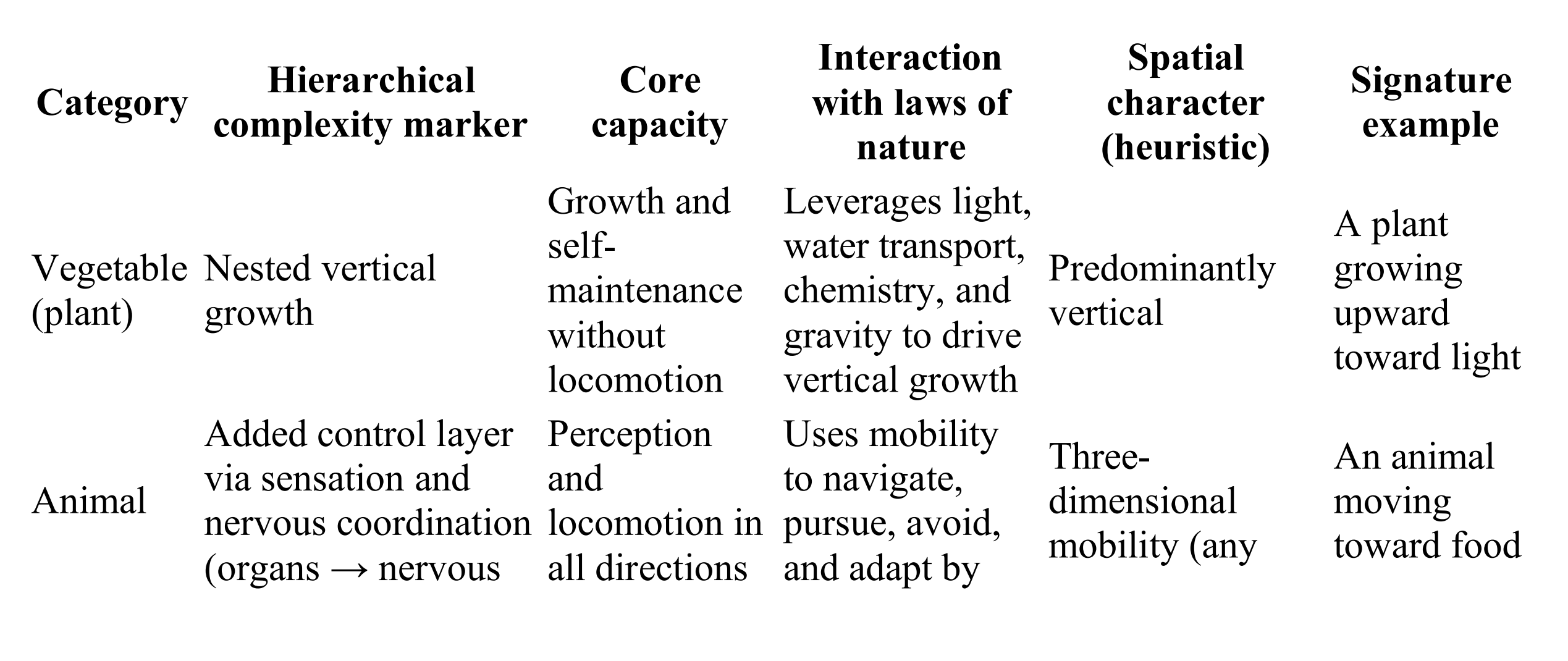

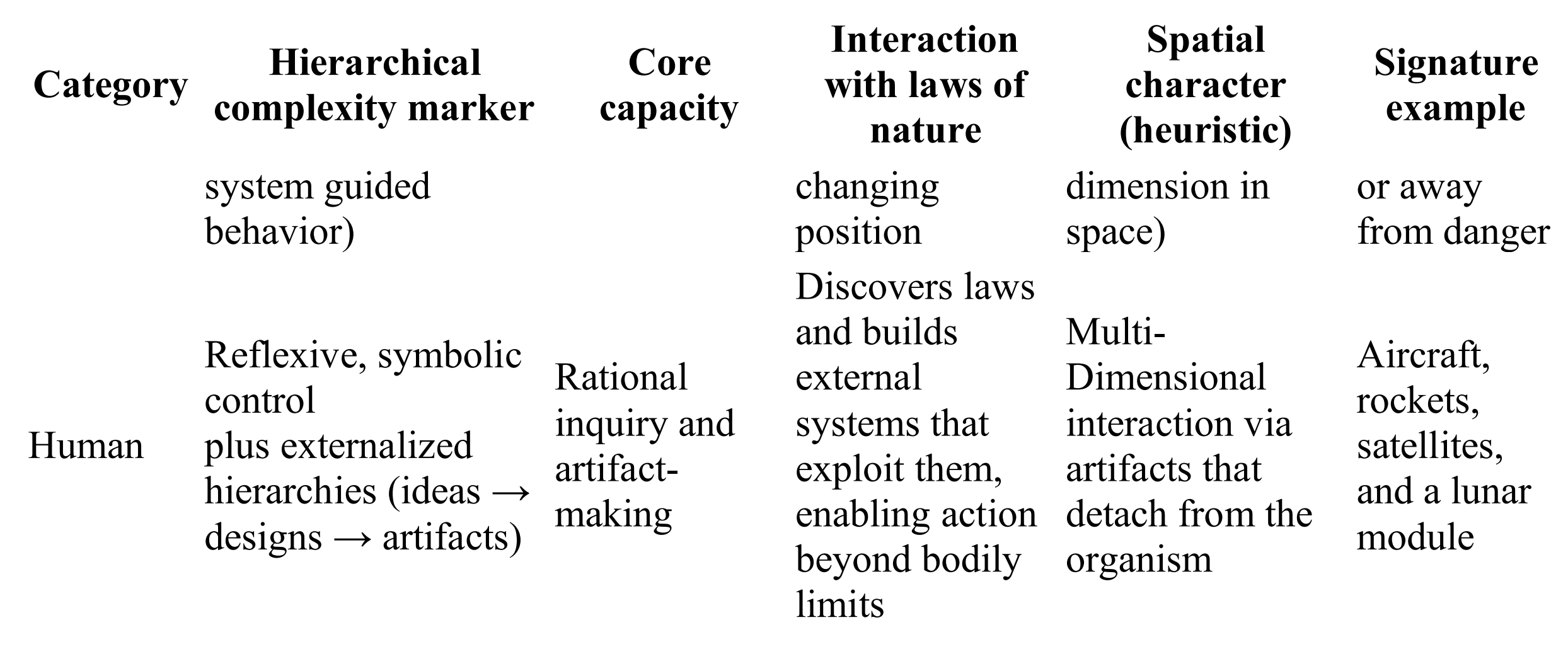

Aristotle’s biological writings offer a precedent for functional classification: minerals, plants,

animals, and humans are distinguished by characteristic powers rather than by mere physical

arrangement. Plants exhibit nutrition, growth, and reproduction. Animals add sensation, appetite,

and self-initiated motion. Humans add rational thought, deliberation, and purposive choice, so

each level is marked by what it can do.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá extends this template by asking how these biological powers position beings in

relation to nature’s law itself. Minerals display regularity under physical forces without using

those regularities toward ends. Plants channel natural regularities into growth and reproduction

without reflective awareness of the laws they express. Animals engage causal regularities

through perception, instinct, and flexible behavior, yet typically without an abstract grasp of

governing principles. Humans, on the other hand, formulate and test regularities, then redirect

their operation toward chosen purposes.

This can be framed as hierarchical complexity: higher forms add control layers that integrate and

govern lower-level processes. Plants exhibit a one-dimensional nested vertical growth, seemingly

defying gravity. Animals add a multi-level dynamic coordination and movement in all directions,

through sensation, nervous control, and locomotion. Humans add symbolic representation and

externalize it into artifacts that exploit natural law independently and externally to the body,

extending organized control into tools, machines, and engineered systems.

Together, these considerations suggest a methodological shift: rather than treating “complexity”

as whatever a particular audience happens to find unnatural, we should ask whether the criterion

for complexity and its division into different hierarchical categories holds across multiple

observers and is anchored in observer-independent standards.

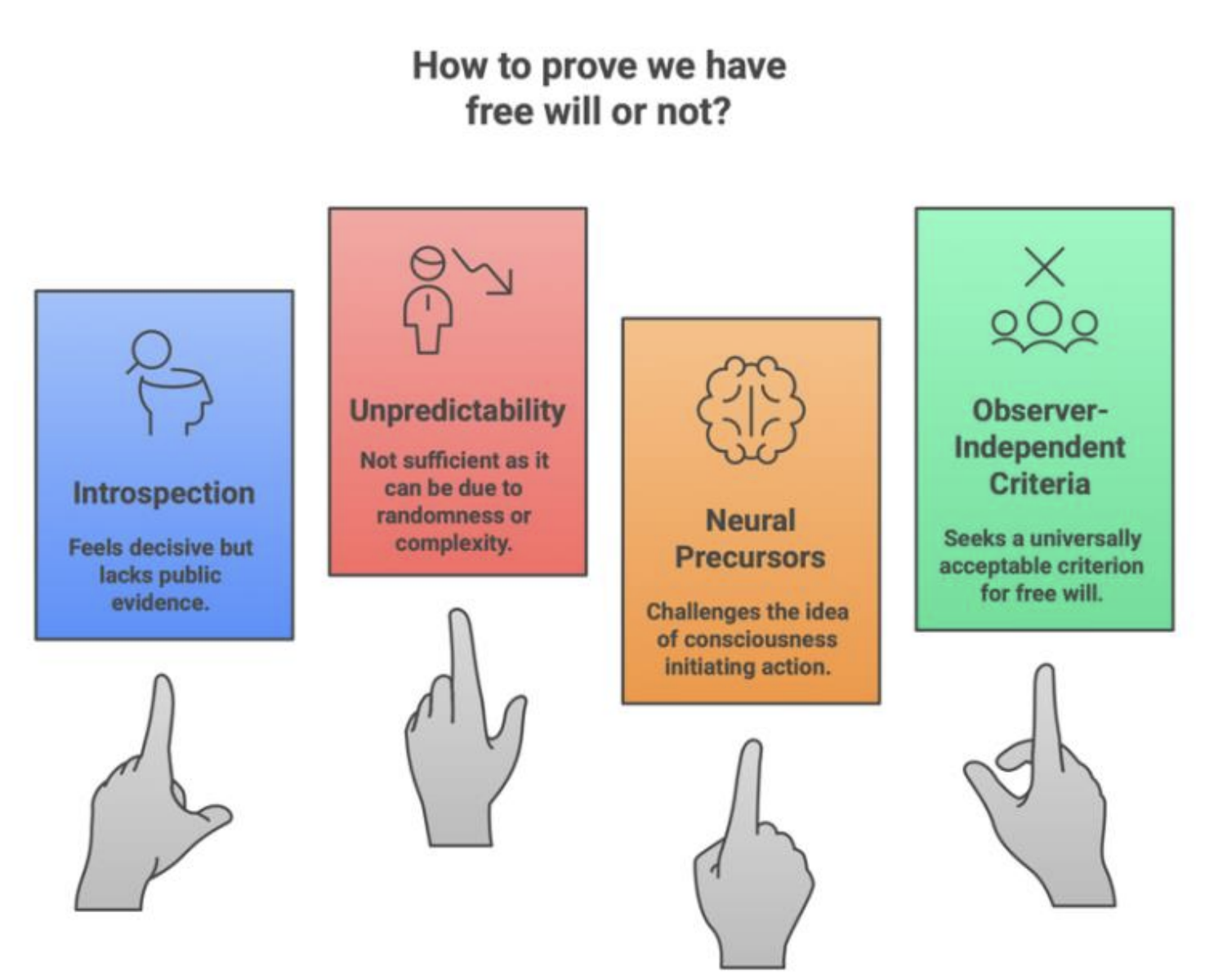

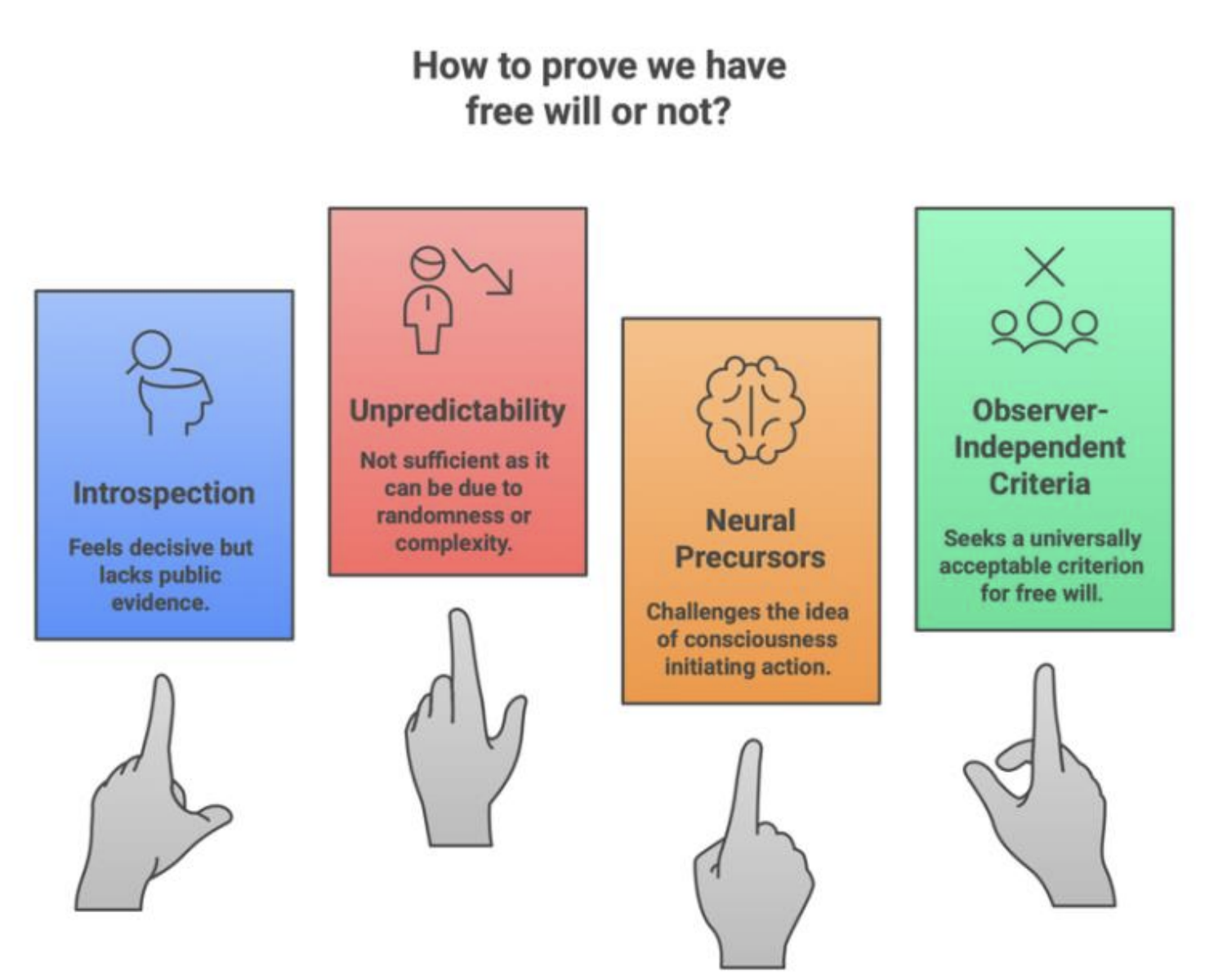

## Free Will: Real or an Illusion?

A natural next step is to move from the complexity of structure and law-governed interaction to a

deeper question about agency:

How do we know we have free will, and how could we prove it?

The challenge is methodological. Introspection feels decisive, yet private conviction rarely

counts as public evidence. At the same time, outward behavior is observable, but many different

causes can generate behavior. If the aim is an account that any competent observer can assess,

the question becomes:

What observable markers would distinguish genuine agency from the appearance of choice

produced by other mechanisms?

One temptation is to treat unpredictability as proof of freedom of choice. If an entity’s behavior

cannot be predicted, one might infer that it has free will. But unpredictability is not enough. A

process can be unpredictable because it is driven by stochastic factors, hidden variables, and

chaotic sensitivity to initial conditions. Randomness can defeat prediction without adding

agency. An outcome that no one could foresee may still be the output of blind chance, or of

lawful dynamics too complex to track. So a test that rests only on failed prediction will

misclassify both random systems and opaque deterministic systems as “free.”

A second temptation moves the other way: some experiments report neural activity that precedes

a person’s conscious report of deciding, prompting skeptics to conclude that free will is illusory.

On this view, we experience deliberation, but the causal machinery is already completed before

awareness registers the choice. This interpretation risks rendering free will effectively

unfalsifiable, since any decision can be dismissed as post hoc awareness of a prior process.

This brings the discussion back to the earlier theme of observer-independent criteria. If structural

complexity can be observer-relative, and non-agentive causes can explain unpredictability, then

the core task is to find a universally acceptable definition of free will: a criterion that does not

depend on a particular culture’s intuitions, or on a specific species’ psychology, but can be

applied across observers who share access to the same laws of nature. The guiding question then

becomes:

What would count, for any observer, as evidence that a system is not merely pushed around by

law or noise, but can govern its own action within the natural law?

Together, these considerations suggest a methodological shift: rather than treating “complexity”

as whatever a particular audience happens to find unnatural, we should ask whether the criterion

for complexity and its division into different hierarchical categories holds across multiple

observers and is anchored in observer-independent standards.

## Free Will: Real or an Illusion?

A natural next step is to move from the complexity of structure and law-governed interaction to a

deeper question about agency:

How do we know we have free will, and how could we prove it?

The challenge is methodological. Introspection feels decisive, yet private conviction rarely

counts as public evidence. At the same time, outward behavior is observable, but many different

causes can generate behavior. If the aim is an account that any competent observer can assess,

the question becomes:

What observable markers would distinguish genuine agency from the appearance of choice

produced by other mechanisms?

One temptation is to treat unpredictability as proof of freedom of choice. If an entity’s behavior

cannot be predicted, one might infer that it has free will. But unpredictability is not enough. A

process can be unpredictable because it is driven by stochastic factors, hidden variables, and

chaotic sensitivity to initial conditions. Randomness can defeat prediction without adding

agency. An outcome that no one could foresee may still be the output of blind chance, or of

lawful dynamics too complex to track. So a test that rests only on failed prediction will

misclassify both random systems and opaque deterministic systems as “free.”

A second temptation moves the other way: some experiments report neural activity that precedes

a person’s conscious report of deciding, prompting skeptics to conclude that free will is illusory.

On this view, we experience deliberation, but the causal machinery is already completed before

awareness registers the choice. This interpretation risks rendering free will effectively

unfalsifiable, since any decision can be dismissed as post hoc awareness of a prior process.

This brings the discussion back to the earlier theme of observer-independent criteria. If structural

complexity can be observer-relative, and non-agentive causes can explain unpredictability, then

the core task is to find a universally acceptable definition of free will: a criterion that does not

depend on a particular culture’s intuitions, or on a specific species’ psychology, but can be

applied across observers who share access to the same laws of nature. The guiding question then

becomes:

What would count, for any observer, as evidence that a system is not merely pushed around by

law or noise, but can govern its own action within the natural law?

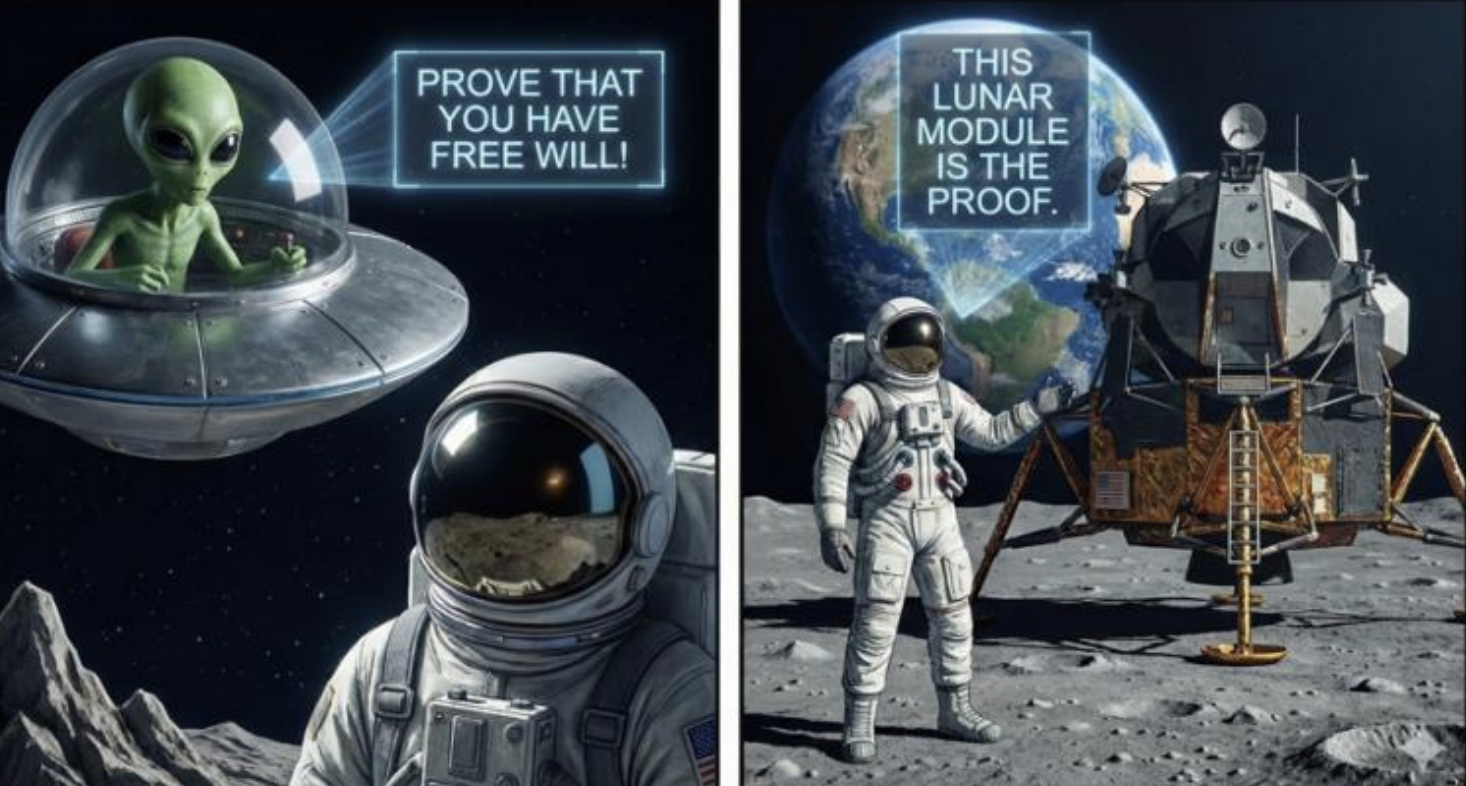

‘Abdu’l-Bahá has given us a definition of free will:

“Likewise every arrangement and formation that is not perfect in its order we designate as

accidental, and that which is orderly, regular, perfect in its relations and every part of which is

in its proper place and is the essential requisite of the other constituent parts, this we call a

composition formed through will and knowledge.” [ 4 ]

Combining this definition with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s framing of complexity as the manner of its

dynamic interaction with laws of nature, we can create a plausible definition and a universal

criterion for free will:

Free will is the capacity of an agent to organize multiple interdependent components into a

holistic system that can harness and leverage natural laws to operate against nature’s local

tendencies.

The search for free will thus parallels the earlier shift from configuration-based to behavior-

based analysis. This framework establishes universal criteria for detecting free will : observing a

module escape a distant planet’s gravitational force through a telescope warrants a conclusion

that its creator possesses free will. These criteria remain compatible with natural law while

pointing to a higher-order mode of control that unpredictability alone cannot capture.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá has given us a definition of free will:

“Likewise every arrangement and formation that is not perfect in its order we designate as

accidental, and that which is orderly, regular, perfect in its relations and every part of which is

in its proper place and is the essential requisite of the other constituent parts, this we call a

composition formed through will and knowledge.” [ 4 ]

Combining this definition with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s framing of complexity as the manner of its

dynamic interaction with laws of nature, we can create a plausible definition and a universal

criterion for free will:

Free will is the capacity of an agent to organize multiple interdependent components into a

holistic system that can harness and leverage natural laws to operate against nature’s local

tendencies.

The search for free will thus parallels the earlier shift from configuration-based to behavior-

based analysis. This framework establishes universal criteria for detecting free will : observing a

module escape a distant planet’s gravitational force through a telescope warrants a conclusion

that its creator possesses free will. These criteria remain compatible with natural law while

pointing to a higher-order mode of control that unpredictability alone cannot capture.

## Identifying Intelligent Causation

A persistent weakness in Intelligent Design argumentation is its reliance on contested notions of

“complexity” and “function.” What counts as complex often reflects intuitive impressions rather

than consistently applicable criteria across various contexts and observers. “Function” can be

assigned retrospectively once a structure is known, risking hindsight bias. The result is a

framework that appears compelling to those sharing its intuitions while remaining

methodologically fragile to others.

Darwinian theory avoids some pitfalls by tying function to differential contribution to survival

and reproduction. Yet as a general account of complexity, evolutionary discourse can remain

imprecise. Complexity may refer to the number of parts, interdependence, information content,

hierarchical organization, or pathway length, meanings that don’t always converge. This

ambiguity weakens attempts to use “complexity” as a term for broader philosophical

conclusions.

## Identifying Intelligent Causation

A persistent weakness in Intelligent Design argumentation is its reliance on contested notions of

“complexity” and “function.” What counts as complex often reflects intuitive impressions rather

than consistently applicable criteria across various contexts and observers. “Function” can be

assigned retrospectively once a structure is known, risking hindsight bias. The result is a

framework that appears compelling to those sharing its intuitions while remaining

methodologically fragile to others.

Darwinian theory avoids some pitfalls by tying function to differential contribution to survival

and reproduction. Yet as a general account of complexity, evolutionary discourse can remain

imprecise. Complexity may refer to the number of parts, interdependence, information content,

hierarchical organization, or pathway length, meanings that don’t always converge. This

ambiguity weakens attempts to use “complexity” as a term for broader philosophical

conclusions.

The Bahá’í framework proposes a more observer-independent approach by shifting attention

from static arrangements to law-governed interactions. Design is best detected not merely by

intricate configuration, but by organized systems that exploit nature’s regularities to achieve ends

running counter to local natural law tendencies. Within this Bahá’í framework, design can be

defined operationally as follows:

An artifact is designed by an intelligent agent if it comprised of multiple interdependent

components arranged into a holistic system that harnesses natural laws to operate against

nature’s local tendencies.

Two features matter. First, the criterion anchors in natural law, supplying a universal reference

point for any observer, anywhere. Second, it focuses on capacity rather than historical pathways.

Design detection infers an organized agency expressed through dynamic interaction with nature’s

laws, not a substitute for mechanistic explanations.

This framework doesn’t treat design language as a replacement for biology, geology, genetics, or

other empirical disciplines. Natural inquiry into evolutionary history, causal mechanisms, and

ecological constraint remains valid. The aim is narrower: articulating criteria under which

“design” constitutes disciplined inference about organized agency while leaving intact the

scientific work of reconstructing how organisms and environments change over time.

The Bahá’í approach (as interpreted by the author) also aligns with scientific realism, which

infers unobservables - electrons, quarks, fields - from measurable effects. Methodological

naturalism and scientific realism need not be rivals: the former governs the investigation of

lawful processes; the latter justifies inference beyond direct observation. Detecting design

attempts to unite these commitments: accepting nature’s and life’s evolutionary story while

refining when and how claims of an intelligent agent are warranted.

## Conclusion

This article moved from debates about biological order and probability to a more disciplined

approach to design, complexity, and agency. It argued that design reasoning falters when

evolution is treated as a uniform random search, and improves when it focuses on cumulative

pathways, independent specification, and the limits of after-the-fact inference. Building on

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s insights, it then added a dimension often neglected in both ID and Darwinian

discussions: shifting emphasis from static configuration to dynamic behavior, or how beings and

artifacts engage natural laws. Using an Aristotelian functional hierarchy extended by this law-

engagement lens, this article proposed an interpretation that gravitates towards a more observer-

independent criterion of complexity. The resulting method treats design detection as identifying

organized systems that harness universal laws to counter local tendencies, while fully preserving

the scientific project of explaining evolutionary history.

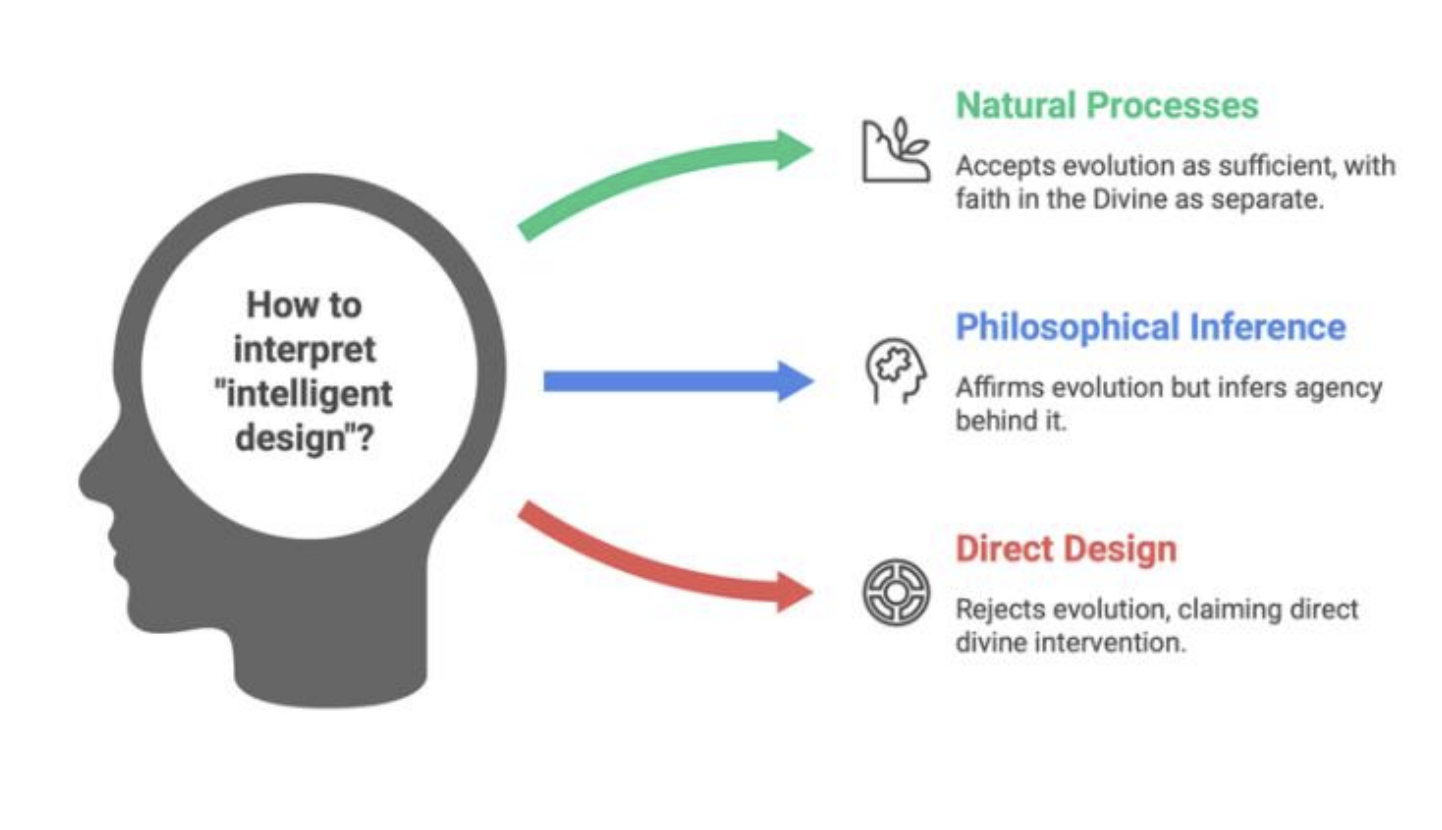

Within this framework, “intelligent design” allows at least three readings. One holds that the

Divine created a lawful cosmos that unfolds through natural processes, yielding life through

evolution. Many naturalists can accept the explanatory sufficiency of those processes while

treating belief in the Divine as faith rather than science. A second reading agrees with the

scientific account of life’s development while arguing that philosophical reasoning can still

justify an inference to agency behind those processes, so design is “detected” without displacing

biology. A third reading aligns with the Intelligent Design movement: natural processes are

deemed inadequate, life is treated as directly designed, and mainstream conclusions are rejected,

often without a comparably detailed, testable alternative.

The Bahá’í framework proposes a more observer-independent approach by shifting attention

from static arrangements to law-governed interactions. Design is best detected not merely by

intricate configuration, but by organized systems that exploit nature’s regularities to achieve ends

running counter to local natural law tendencies. Within this Bahá’í framework, design can be

defined operationally as follows:

An artifact is designed by an intelligent agent if it comprised of multiple interdependent

components arranged into a holistic system that harnesses natural laws to operate against

nature’s local tendencies.

Two features matter. First, the criterion anchors in natural law, supplying a universal reference

point for any observer, anywhere. Second, it focuses on capacity rather than historical pathways.

Design detection infers an organized agency expressed through dynamic interaction with nature’s

laws, not a substitute for mechanistic explanations.

This framework doesn’t treat design language as a replacement for biology, geology, genetics, or

other empirical disciplines. Natural inquiry into evolutionary history, causal mechanisms, and

ecological constraint remains valid. The aim is narrower: articulating criteria under which

“design” constitutes disciplined inference about organized agency while leaving intact the

scientific work of reconstructing how organisms and environments change over time.

The Bahá’í approach (as interpreted by the author) also aligns with scientific realism, which

infers unobservables - electrons, quarks, fields - from measurable effects. Methodological

naturalism and scientific realism need not be rivals: the former governs the investigation of

lawful processes; the latter justifies inference beyond direct observation. Detecting design

attempts to unite these commitments: accepting nature’s and life’s evolutionary story while

refining when and how claims of an intelligent agent are warranted.

## Conclusion

This article moved from debates about biological order and probability to a more disciplined

approach to design, complexity, and agency. It argued that design reasoning falters when

evolution is treated as a uniform random search, and improves when it focuses on cumulative

pathways, independent specification, and the limits of after-the-fact inference. Building on

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s insights, it then added a dimension often neglected in both ID and Darwinian

discussions: shifting emphasis from static configuration to dynamic behavior, or how beings and

artifacts engage natural laws. Using an Aristotelian functional hierarchy extended by this law-

engagement lens, this article proposed an interpretation that gravitates towards a more observer-

independent criterion of complexity. The resulting method treats design detection as identifying

organized systems that harness universal laws to counter local tendencies, while fully preserving

the scientific project of explaining evolutionary history.

Within this framework, “intelligent design” allows at least three readings. One holds that the

Divine created a lawful cosmos that unfolds through natural processes, yielding life through

evolution. Many naturalists can accept the explanatory sufficiency of those processes while

treating belief in the Divine as faith rather than science. A second reading agrees with the

scientific account of life’s development while arguing that philosophical reasoning can still

justify an inference to agency behind those processes, so design is “detected” without displacing

biology. A third reading aligns with the Intelligent Design movement: natural processes are

deemed inadequate, life is treated as directly designed, and mainstream conclusions are rejected,

often without a comparably detailed, testable alternative.

Caution is warranted before drawing hard conclusions. Several key questions remain empirically

open, and future evidence may sharpen what we can claim. If scientists eventually generate

living systems from basic ingredients, from scratch, that would make “natural sufficiency”

concrete rather than speculative. Likewise, more powerful computer simulations of early-Earth

chemistry can stress-test origin pathways, probing how lifelike organization might arise under

plausible constraints and whether natural processes can yield systems that harness universal laws

to counter local tendencies.

Disagreement about “design” often turns less on the term than on which reading of it is assumed.

The Bahá’í-oriented approach developed here aims to preserve scientific explanation while

clarifying when a design inference could be warranted as a philosophical conclusion grounded in

observer-independent criteria tied to natural law.

[1] Tablet to August Forel Page 16

[2] Tablet to August Forel Page 23

[3] Tablet to August Forel Page 11

[4] Tablet to August Forel Page 23

Caution is warranted before drawing hard conclusions. Several key questions remain empirically

open, and future evidence may sharpen what we can claim. If scientists eventually generate

living systems from basic ingredients, from scratch, that would make “natural sufficiency”

concrete rather than speculative. Likewise, more powerful computer simulations of early-Earth

chemistry can stress-test origin pathways, probing how lifelike organization might arise under

plausible constraints and whether natural processes can yield systems that harness universal laws

to counter local tendencies.

Disagreement about “design” often turns less on the term than on which reading of it is assumed.

The Bahá’í-oriented approach developed here aims to preserve scientific explanation while

clarifying when a design inference could be warranted as a philosophical conclusion grounded in

observer-independent criteria tied to natural law.

[1] Tablet to August Forel Page 16

[2] Tablet to August Forel Page 23

[3] Tablet to August Forel Page 11

[4] Tablet to August Forel Page 23